Explainer 8:

The Guerrilla Roster

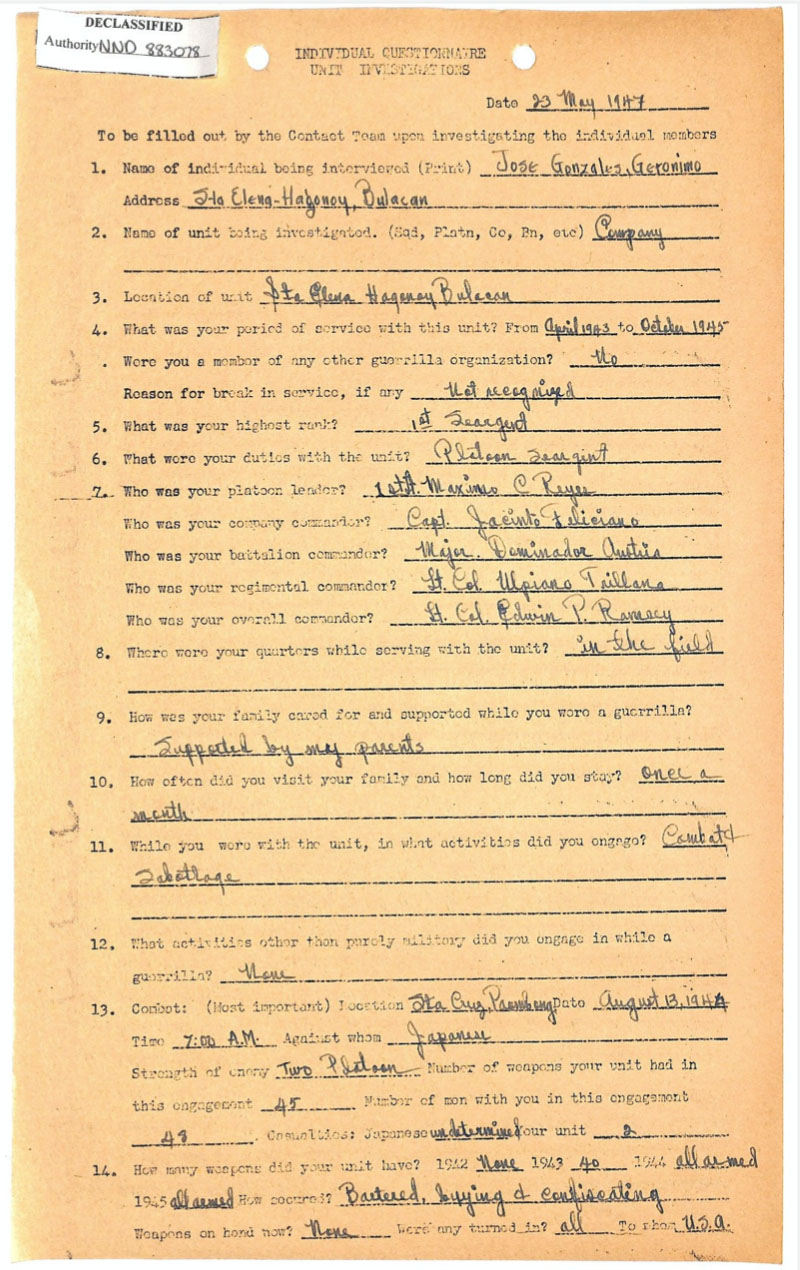

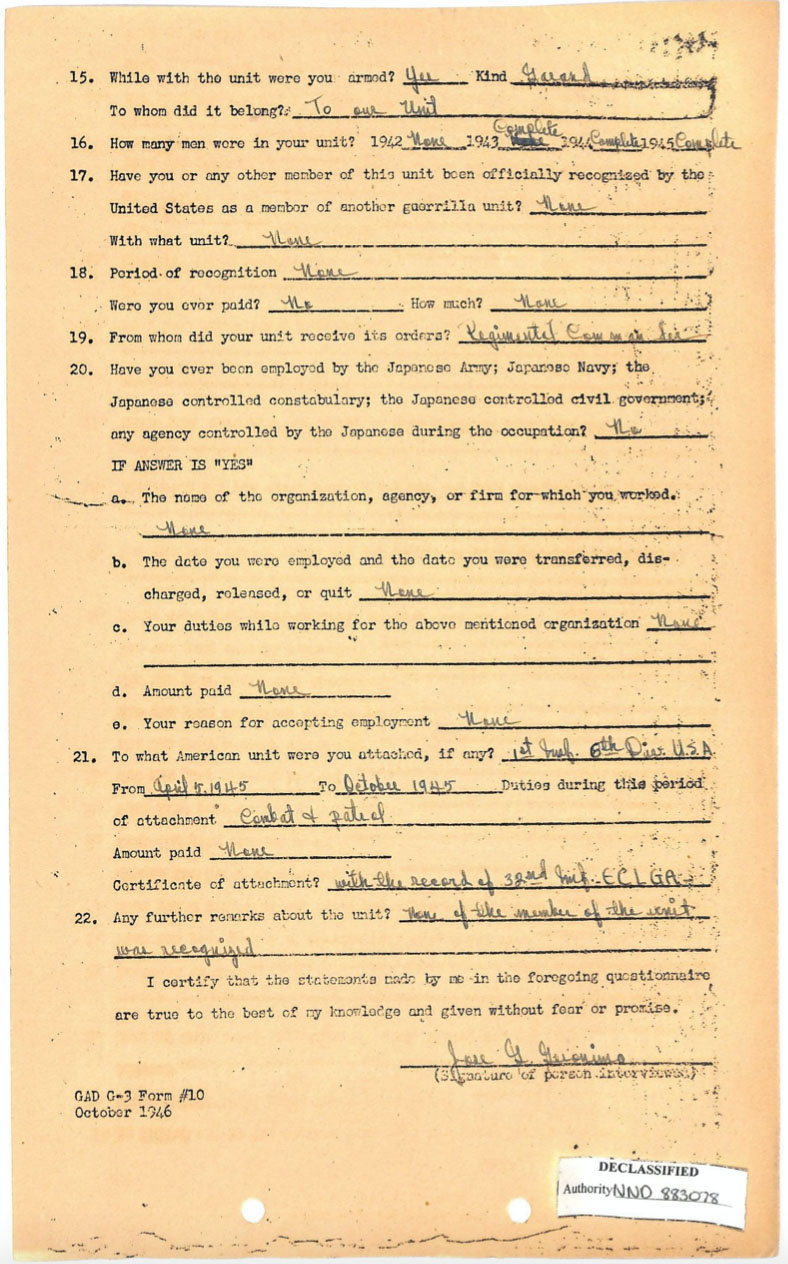

A declassified questionnaire with a Filipino guerrilla leads to an examination of the historical importance of the little-known “Guerrilla Roster” from the Philippines in World War II.

Teacher Background

Among the most important and fascinating historical documents from World War II is the roster of Filipino guerrillas. Because it was classified for almost 75 years, the guerrilla roster is little known by most Americans, but it’s a key part of the story of the war in the Philippines and the fight for justice and equity for Filipino veterans.

As many as 260,000 Filipinos served as guerrillas during World War II. Some served in large and well-organized forces that functioned like armies and stayed in close contact with U.S. military’s temporary headquarters in Australia. Such units included Filipinos trained by the U.S. armed forces and American soldiers who stayed behind. Others built guerrilla movements from the grassroots. They had little experience and few connections to the U.S. military, but they mobilized peasants’ discontent toward their landlords and drew on the long tradition of Filipino nationalism that dated back to the revolution of the 1890s. Many sought revenge against Japanese occupiers for their atrocities against Filipino civilians. Some units allowed women to serve; many women served as nurses and filled other crucial non-combatant roles, though Filipina women did serve in combat roles, and at a higher rate than in many other theaters of the war. General MacArthur, from his command in Australia, declared that members of the organized guerrilla groups were part of the United States Armed Forces of the Far East (USAFFE). The status of outlaw guerrilla groups was less clear.

Guerrillas collected intelligence and undermined the Japanese. They used the tools of guerrilla warfare: hit-and-run ambushes, sniper attacks, and kidnappings that targeted Japanese soldiers on patrol. Guerrillas sabotaged Japanese military equipment and infrastructure. Guerrillas depended on local civilians for food, shelter, and intelligence.

In June 1945, after the liberation of the Philippines, the Americans established the “Recovered Personnel Division” (RDP) to locate, recover and take care of U.S. and other Allied military and civilian personnel who had been captured by the Japanese. The RDP was also tasked with gathering personal information on civilians employed by the Army during the war, guerrillas and POWs. The RDP’s records would be key to determining who had served in the war, and therefore who was owed pay, pensions and other benefits. They were also often the only records of Filipina women’s service in the war effort.

The RDP records, especially those concerning guerrillas, are fascinating. Typically U.S. military records were much more organized, but the nature of the conflict in the Philippines, where most of the trained American military withdrew, leaving behind POWs and guerrilla fighters, meant that wartime records had to be assembled after-the-fact. Documents produced during the war indicate the wartime paper shortage: records were often recorded on brown paper bags or on the backs of letters, sales receipts, court documents, and food labels. More than 350,000 people, civilians and guerrillas, were interviewed by the RDP after the war. The Philippine Archives Collection, now housed at the U.S. National Archives, totals 1,665 boxes.

In 1949, the U.S. classified the guerrilla roster. This meant that the thousands of Filipino men and women who fought with the guerrillas had no documentation of their service. Further, it meant it was impossible for these veterans to claim benefits. It was only in 2009, after the Filipino Veterans Equity Compensation Fund was established, that the guerrilla roster was declassified. Retired Major General Antonio Taguba was key to the effort to release these records, pressing the Army and the V.A. for documents that would help veterans prove their eligibility for compensation.

In 2015, the government of the Philippines sent a team of archivists to the United States to digitize the collections; due to time and financial constraints, they only digitized the guerrilla roster (about 270 boxes and 270,000 documents). These digital records were posted online by the Philippine military, so that veterans and descendants based in the Philippines don’t have to travel to Washington, D.C. to find these important service records. The digitized collection can be found here.

Note: “Roster” is sort of a misleading term; it sounds as if there’s one long list of all people who fought as guerrillas, when in fact there are thousands of pages, corresponding to hundreds of units. The roster includes lists of those who served, questionnaires with guerrillas, histories of each unit’s wartime service, and U.S. Army personnel’s recommendations for whether or not to recognize the service of the units.

Suggested Teaching Strategies

- Start by reviewing the experiences and contributions of guerrillas in the Philippines during World War II. Be sure to emphasize the risk that guerrillas took by resisting the Japanese, and to review the kinds of services guerrillas performed. If time allows, students can read through the online exhibit Under One Flag, which includes oral history interviews, primary sources and background information on Filipino guerrillas.

- Ask students to carefully examine the questionnaire with Jose Gonzales Geronimo, who was part of a guerrilla unit in the East Luzon Guerrilla Area during the war (you may want to have students identify Luzon on a map). The focus questions will help them draw out information from the record.

- After examining the document, share details from the Teacher Background, above, about why and when this record was created and the larger context of the guerrilla roster. Discuss with students the stakes of the guerrilla roster’s classification and declassification, especially as it relates to compensation for Filipino veterans.

- We strongly suggest pairing a look at the historical document below with listening to one or more of the oral histories of Filipino veterans who served as guerrillas, especially that of Celestino Almeda. Almeda was a long-time activist for Filipino veterans’ recognition and equity; he received the Congressional Gold Medal in 2017 at the age of 103 and spoke at the ceremony in Washington, D.C. Ciriaco Ladines, one of the 7,000 “Anderson Guerrillas” who refused to surrender at Bataan and organized under Lt. Col. Bernard Anderson, also recounts combat as a veteran; we recommend using clips of his interviews with students.

- If time allows, have students comb through the digitized Philippines Archive Collection and look for examples of different kinds of service performed by the guerrillas and the general difficulties of life in the occupied Philippines.

Curriculum Standards

Common Core: Middle School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.9 Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic.

Common Core: High School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.9 Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

Individual Questionnaire of Jose Gonzales Geronimo, 1947

After the war, the U.S. military set about collecting records of wartime service in the Philippines. Between 1945 and 1949, they interviewed approximately 350,000 people, the vast majority of them guerrillas. The records include lists of guerrillas, questionnaires, short histories of guerrilla units’ wartime experiences, and Army personnel’s recommendations about whether or not to recognize each unit’s service. The records were classified in 1949 and remained so until 2009, when they were declassified so that Filipino veterans could prove their eligibility for payments from the Filipino Veterans Equity Compensation Fund. This is one such record from the vast guerrilla roster.

Source: 32nd Infantry Regt., Bataan Military District (BMD), East Central Luzon Guerrilla Area (ECLGA), File Number 308-20, Box Number 507, National Archives ID 1431822, 1941-1948; online at Philippine Archives Collection

Focus Questions

- What kind of service did Jose Gonzales Geronimo perform as a guerrilla? How long was he a guerrilla?

- What kind of weapons did Jose’s unit have, and how were they acquired?

- How did the conditions for Gonzales’ unit change over the course of the war?

- What was the effect of classification of this and other records from the guerrilla roster, for Filipino veterans?