Explainer 4:

Japanese Propaganda in the Philippines

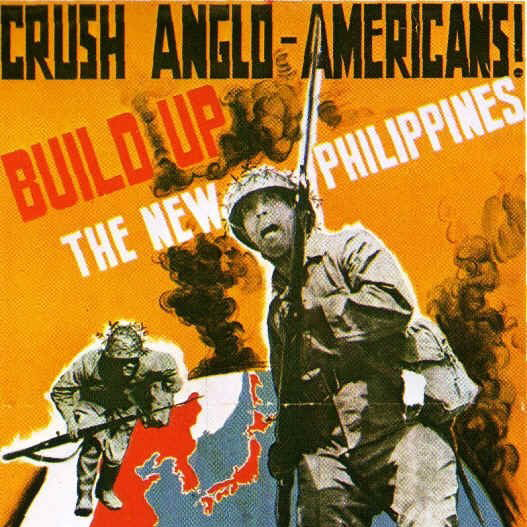

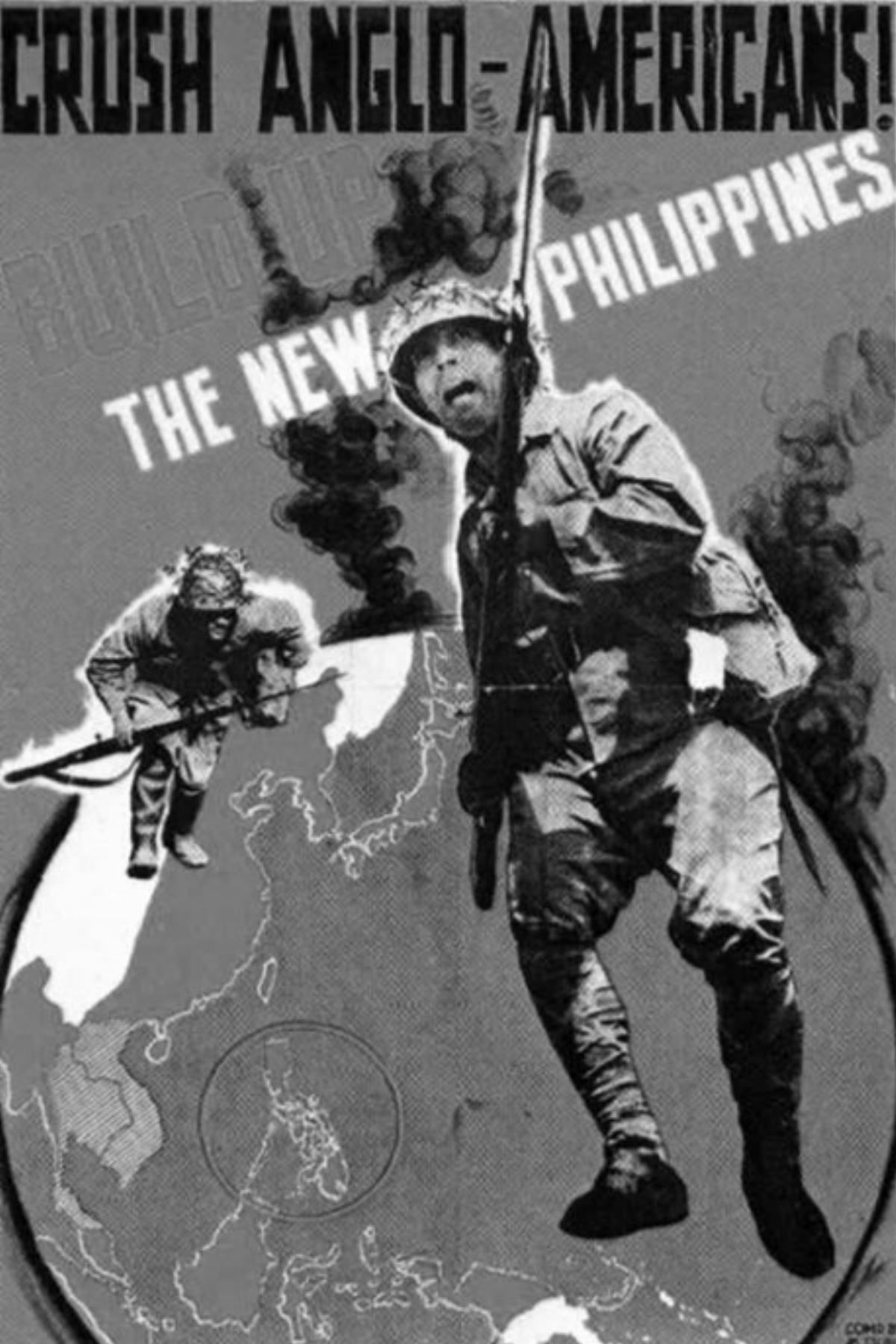

Dueling Propaganda in the Philippines: A poster and a photograph that compare the different propaganda Filipinos navigated from Japan and the U.S. during World War II.

Teacher Background

By May 1942, the Japanese completely occupied the Philippines. For most Filipinos daily life continued, but with new uncertainties. Were the Japanese here to stay? Would the Americans return? Families scrambled to find food, gas, medicine and other supplies; as the war went on, food shortages were a major issue throughout the islands.

The Japanese promised a “Bagong Araw,” or “New Era,” and called for an age of “Asia for Asians.” Some Filipinos cooperated with the occupiers, either in hopes that the Japanese would be more supportive of an independent Philippines, and others to get rich by working with the Japanese. In October 1943, Japan even granted independence to the Philippines. Emilio Aguinaldo, hero of the wars against Spain and the United States in 1898, was on hand to raise the flag of the Second Philippine Republic. Longtime judge José Laurel was appointed as president. “The offer of independence could not have been rejected,” he later wrote. “Our ancestors had fought for it.”

But despite messages of cooperation and prosperity, the Japanese were foreign occupiers and the country was at war. Japanese forces fanned out to occupy cities and villages across the islands. Military police and a network of informants kept a close eye on ordinary citizens, and carefully censored their publications while filling the airwaves with propaganda broadcasts. The Japanese executed Filipinos who were caught aiding guerillas (local masked informers were tasked with pointing out collaborators); the Japanese also committed retaliatory executions of civilians for guerilla activity.

To counter Japanese propaganda and censorship, the Filipino resistance, with the help of Americans, built their own information-sharing networks. Illegal broadcasts and underground newspapers reported the actual progress of the war, including American advances in the Pacific, and boosted morale. These messages reported and reassured Filipinos that guerillas were fighting the Japanese and that the Americans would return.

If caught with underground newspapers like “The Liberator” or illegal shortwave radios, the consequences would be deadly. Filipinos risked their lives to produce and share news and to stay in touch with American forces during the war. Filipinos made their own ink; paper was scarce, so surviving newspapers are often printed on the reverse of other items.

The Japanese poster in this explainer attempts to rally pan-Asian sentiment and inspire anti-American feelings among Filipinos. Other examples of Japanese propaganda can be found in the Under One Flag exhibit.

Suggested Teaching Strategies

-

Introduce the activity by tapping students’ prior knowledge about propaganda during war, or introducing the major appeals that most propaganda uses: Emotional, Appeals to Fear, Patriotism, Nationalism, Demonization/Name-Calling, Bandwagon, etc. Review with students that propaganda uses symbols, images and words to convey its messages.

-

Ask students to use the focus questions to analyze the primary source and weigh the risks and rewards of buying into either Japanese propaganda during the war.

-

To learn more about life under Japanese occupation, have students review the “Occupation” section of Under One Flag. Ask students to find additional examples of Japanese propaganda from the war, as well as examples of how Filipinos resisted the Japanese, including by producing their own media (radio and newspapers). Have students assess the risks and rewards of buying into Japanese propaganda and cooperating with Japanese occupiers, versus resistance.

-

Sonny Izon, son of a veteran and activist, recounts his father’s work to produce The Liberator. This story is brought to life in an animation in the exhibit.

Curriculum Standards

Common Core: Middle School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.6 Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts).

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.7 Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts.

Common Core: High School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including analyzing how an author uses and refines the meaning of a key term over the course of a text.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.7 Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem.

Japanese Propaganda in the Philippines

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, both the Japanese and the Americans broadcast messages to Filipino civilians. Japanese posters, newspapers and radio broadcasts promised a “Barong Araw,” or “New Era,” and called for “Asia for Asians.” Actual news of the war, including the Americans’ advancing progress in the Pacific, was heavily censored.

Sources: Japanese propaganda poster, 1942.

Focus Questions

-

Who created the poster and for what purpose? Who was its intended audience?

-

What kind of appeal(s) are the creators making?

-

Do you think this propaganda would have been persuasive to Filipinos? Why or why not?