Lesson Plan 4:

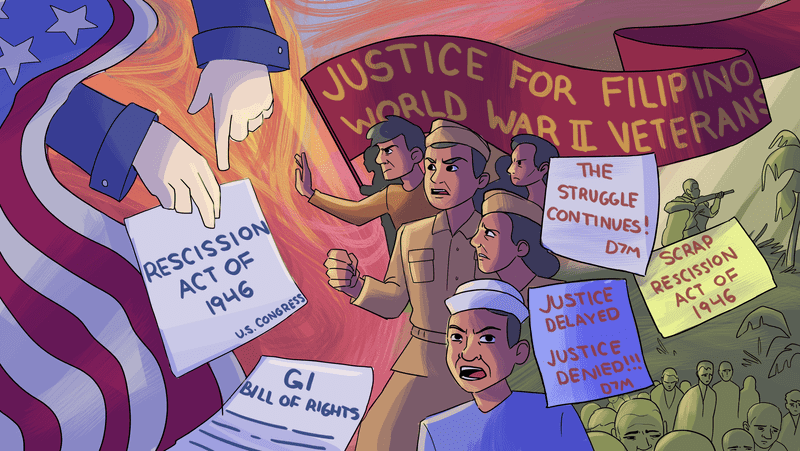

Putting the Rescission Act on Trial

In this lesson, students prepare to put the 1946 Rescission Act on trial for unfairly stripping Filipino veterans of the benefits they had earned as members of the U.S. armed forces in World War II. To prepare their cases, students review a variety of primary sources and determine what evidence to present and which witnesses to call. Note: These primary sources can be adapted to create a Document-Based Question for A.P. or I.B. students.

Summary

Students prepare for and conduct a mock trial of the 1946 Rescission Act by reviewing up to 14 primary sources to find evidence; can be adapted to create a DBQ.

U.S. History | High School | 2-3 class periods

Materials

- Student Instructions

- Primary Source Packet (14 documents)

- Optional: Access to online exhibit Under One Flag”

Grade Level/Subject

Middle School or High School U.S. History, High School World History (For younger students, you may want to adapt the number of primary sources being used.)

Common Core: Middle School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.6 Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts).

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.7 Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.8 Distinguish among fact, opinion, and reasoned judgment in a text.

Common Core: High School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.3 Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.5 Analyze in detail how a complex primary source is structured, including how key sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text contribute to the whole.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.6 Evaluate authors’ differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by assessing the authors’ claims, reasoning, and evidence.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.9 Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.8 Evaluate an author’s premises, claims, and evidence by corroborating or challenging them with other information.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.9 Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

UCLA Public History Initiative | US History Content Standards

- Era 9, Standard 2: How the Cold War and conflicts in Korea and Vietnam influenced domestic and international politics

- Era 9, Standard 4: The struggle for racial and gender equality and the extension of civil liberties

- Era 10, Standard 1: Recent developments in foreign and domestic policies

UCLA Public History Initiative | World History Content Standards

- Era 9, Standard 1: How post-WWII reconstruction occurred, new international power relations took shape, and colonial empires broke up.

Teacher Background

At the end of World War II, after years of high government spending to support the war effort, Congress was looking for ways to trim the U.S. budget. In 1946, a “rescission” bill, to rescind or cut funds that had previously been appropriated, was introduced; if passed, it would cut or save the U.S. about $52 billion. Among the costs that budget-conscious Congressmen identified were veterans benefits for Filipinos who had served in the U.S. armed forces during the war. An October 1945 report from the Veterans Administration estimated that the lifetime cost of benefits for Filipinos would be about $3.2 billion.

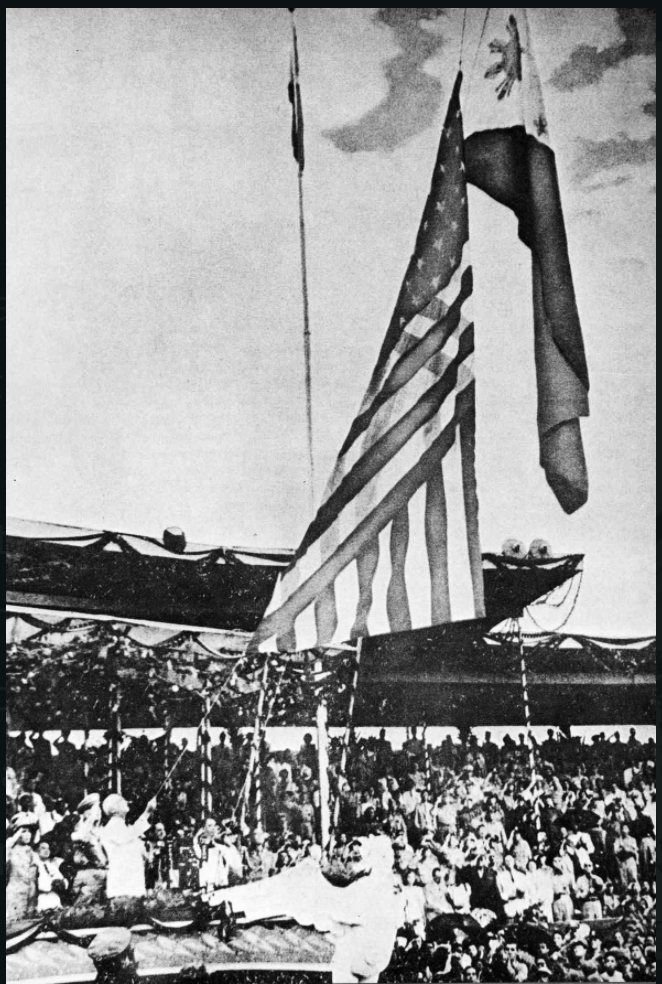

At the same time, the U.S. was set to fulfill the promise of the Tydings-McDuffie Act and finally grant independence to the Philippines. In a solemn ceremony on July 4, 1946, the U.S. flag was lowered and the Philippine Republic’s flag was raised in Manila’s main square. Despite wartime orders from President Roosevelt and General MacArthur making clear that Filipinos who fought for the U.S. were full members of the U.S. armed forces, members of Congress argued that the Philippines now had responsibility for caring for Filipino veterans. To help them do so, Congress added a rider to the rescission bill. It provided a one-time $200 million-dollar payment to the Philippines government to help them provide veterans care. It also stated that Filipinos who served in the U.S. military during the war would henceforth not be considered veterans, and therefore not entitled to any veterans benefits from the United States government.

The confluence of these two events, post-war cost-cutting measures and the declaration of an independent Philippines, was disastrous for Filipino veterans. The 1946 Rescission Act declared that they alone, of all people who had served in the U.S. military during World War II, would be denied veterans benefits.

Compare Filipino veterans’ situation to that of other World War II veterans. Passed unanimously in Congress and signed by FDR in 1944, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, better known as the GI Bill, provided tuition, cost-of-living, books and supplies, equipment and counseling services for veterans to continue their education. It provided government-backed loans so returning veterans could purchase homes. The bill also ensured that veterans’ hospitalization needs would be taken care of. Approximately 8 million veterans received educational benefits over the next seven years, costing about $14.5 billion. By 1955, 4.3 million home loans had been granted, with a face value of $33 billion. The bill also appropriated half a billion dollars for the construction of new veteran hospitals.

Filipino veterans were denied another major benefit, too. In 1940, as the U.S. looked ahead to a possible second world war, Congress had passed the Nationality Act. The law clarified who was eligible for birthright citizenship and outlined the process by which immigrants could become naturalized as U.S. citizens. It specifically stated that foreigners, “including a native-born Filipino,” who had served honorably in the U.S. military could become U.S. citizens. During World War II, servicemembers from more than 60 countries around the world served under the U.S. flag, including 200,000 Filipinos. The terms of the Rescission Act prevented Filipino veterans from being able to pursue U.S. citizenship if they wanted to. (Not helping matters: The U.S. also closed its Immigration & Naturalization Services offices in the Philippines after the handover.)

The Philippines government rejected the offer. Diplomat Carlos P. Romulo testified before the United States Congress in 1948, saying:

The Rescission Act deprives Filipino veterans of veterans’ benefits, with the proviso that $200 million be appropriated to the Army of the Philippines. These $200 million, which are purportedly in lieu of the benefits of which Filipino veterans were thus deprived, are actually not even sufficient to cover their back pay. The Philippine Government has chosen not to accept the appropriation.

The Rescission Act kicked off a 75-year effort by Filipino veterans and their advocates to gain justice. They sought the veterans benefits and healthcare they had earned and, for those that wanted it, the opportunity to obtain citizenship. Filipino veterans also wanted the U.S. to acknowledge the injustice that had been done by the passage of the Rescission Act and lobbied for it to be repealed.

Instructions

1. Introduction (10 minutes): Veteran’s Benefits

Review with students the passage of the GI Bill in 1944, as the U.S. was anticipating the end of the war and feared the mass unemployment of 15 million men and women who had served in the armed forces. Depending on time, you can use document 5 in the Primary Source Packet, which includes a basic summary of the act and the value of benefits in the first decade after the war.

2. Prepare the Case (At least one class period)

There are many ways to structure a mock trial, depending on the time available and students’ sophistication. The simplest strategy is to divide students into two sides, prosecution and defense, with the teacher serving as the judge to whom they’ll present their cases. Allow students at least one full class period to review evidence and build their case, prepare their witnesses, and so forth. Reserve one class period for the trial itself and a debrief discussion with students afterwards.

Divide students into two teams. Every student should get a copy of the instructions for preparing their case and each team should get the full packet of primary sources. In this trial, the prosecution is bringing a case against the Rescission Act that it is an illegal attempt to strip Filipino veterans of their benefits. The defense needs to argue that it was justifiable and therefore legal.

Students will need to decide how to make their arguments, including which evidence to present and what witnesses to call. In their groups, students will assign themselves the roles of lawyers and witnesses. You can also allow students to find other evidence in support of their cases from the Under One Flag exhibit or other reliable sources.

About halfway through the prep time, each side should send a list of which witnesses they plan to call so that the other side can prepare to cross-examine them.

3. Mock Trial (One class period)

Set up the classroom with tables for the opposing sides, a witness stand and an easel or projector for students to display evidence. Run through the basic steps of a trail:

1. Opening Statements (Up to five minutes each)

2. Prosecution’s Evidence

3. Defense’s Evidence

4. Witnesses for the Prosecution and Cross-Examination by the Defense

5. Witnesses for the Defense and Cross-Examination by the Prosecution

6. Closing Arguments

After the trial has concluded, the teacher can decide in favor of one side, based on how well students made their case.

4. Concluding Discussion

Lead students in a discussion reflecting on the trial and their learnings about the Rescission Act. Key questions to address:

a. What did the Rescission Act do? Who was harmed by the Rescission Act, and how?

b. In the trial, what evidence was most persuasive that the U.S. was unjustified in passing the law? What evidence was most persuasive that the U.S. was justified?

c. If the Rescission Act is unjustified or wrong, what’s the remedy? (You can use this discussion to tease the lesson, “You Decide: Filipino Veterans’ Long Fight for Justice,” if you plan to teach it.)

Related Explainers

Student Instructions

Prosecution Legal Team Prep Sheet

You’ve been hired to make the case that the Rescission Act of 1946, which declared that Filipino veterans of World War II were not considered part of the U.S. armed forces for the purposes of receiving benefits, was an unjustifiable and illegal act. To build your case, you’ll have to comb through historical documents, oral histories and other sources to find evidence. You may discover people who can serve as witnesses, who will need to be prepared to answer questions on the witness stand and to be cross-examined by the other side.

Once you find evidence, you’ll have to think about how to present it: What excerpts are most convincing? What context will the judge need to understand why it helps your case? What will the other side try to argue, and how will you counter?

In your legal team, decide who will play each of the following roles:

• Lead Counsel: This person serves as a sort of team captain, helping keep everyone on track and leading the development of your case. This person will also make the opening and closing statements in the trial. You can split this role between two people if needed.

• Co-counselors: This is the rest of your legal team. They will be involved in analyzing historical sources to find convincing evidence, determining what witnesses to call, and designing “exhibits” to present to the judge and preparing witnesses for questioning. Once your team has decided how many witnesses to call, it’s recommended to pair one co-counsel with each witness to prepare for questioning.

• Witnesses: These people will inhabit the character of a real historical person and be called to testify during the case. They’ll need to research the real person’s actual words and actions, as well as find more background information about him or her, in order to build a credible character. The witness should be prepared by co-counselors, who will question them during the trial. In their prep, witness and co-counselor should practice what questions will be asked, as well as anticipate what questions the other side will ask during co-examination. Each side should call at least two witnesses and no more than five.

Your evidence packet includes 14 primary sources. As you read through them, you may decide that more evidence is required to make your case. The online exhibit Under One Flag includes more oral histories, historical documents and background information about the Rescission Act and may be helpful.

Use the graphic organizer to sift through the evidence and build your case.

Prosecution’s Plan

|

Helpful Historical Evidence: Document Name, Key Quotes, and Statistics |

Damaging Historical Evidence: Document Name, Key Quotes, and Statistics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What witnesses do you plan to call? How does each help you prove your case? Where are they vulnerable to an attack from opposing counsel? Which co-counselor will help prepare each witness?

What additional evidence, if you can find it, would be helpful to your case? This may include “smoking gun” historical documents or additional witnesses. Who will be responsible for finding this evidence?

Defense Legal Team Prep Sheet

You’ve been hired to make the case that the U.S. government was justified in passing the Rescission Act of 1946, which declared that Filipino veterans of World War II were not considered part of the U.S. armed forces for the purposes of receiving benefits. To build your case, you’ll have to comb through historical documents, oral histories and other sources to find evidence. You may discover people who can serve as witnesses, who will need to be prepared to answer questions on the witness stand and to be cross-examined by the other side.

Once you find evidence, you’ll have to think about how to present it: What excerpts are most convincing? What context will the judge need to understand why it helps your case? What will the other side try to argue, and how will you counter?

In your legal team, decide who will play each of the following roles:

• Lead Counsel: This person serves as a sort of team captain, helping keep everyone on track and leading the development of your case. This person will also make the opening and closing statements in the trial. You can split this role between two people if needed.

• Co-counselors: This is the rest of your legal team. They will be involved in analyzing historical sources to find convincing evidence, determining what witnesses to call, and designing “exhibits” to present to the judge and preparing witnesses for questioning. Once your team has decided how many witnesses to call, it’s recommended to pair one co-counsel with each witness to prepare for questioning.

• Witnesses: These people will inhabit the character of a real historical person and be called to testify during the case. They’ll need to research the real person’s actual words and actions, as well as find more background information about him or her, in order to build a credible character. The witness should be prepared by co-counselors, who will question them during the trial. In their prep, witness and co-counselor should practice what questions will be asked, as well as anticipate what questions the other side will ask during co-examination. Each side should call at least two witnesses and no more than five.

Your evidence packet includes 14 primary sources. As you read through them, you may decide that more evidence is required to make your case. The online exhibit Under One Flag includes more oral histories, historical documents and background information about the Rescission Act and may be helpful.

Use the graphic organizer to sift through the evidence and build your case.

Defense’s Plan

|

Helpful Historical Evidence: Document Name, Key Quotes, and Statistics |

Damaging Historical Evidence: Document Name, Key Quotes, and Statistics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What witnesses do you plan to call? How does each help you prove your case? Where are they vulnerable to an attack from opposing counsel? Which co-counselor will help prepare each witness?

What additional evidence, if you can find it, would be helpful to your case? This may include “smoking gun” historical documents or additional witnesses. Who will be responsible for finding this evidence?

Primary Source Packet

DOCUMENT 1: “The Fighting Filipinos,” 1943

In mid-1941, anticipating possible war with the Japanese, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called all organized military forces of the Philippine Commonwealth into service of the U.S. military. The United States Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) drew together Philippine Scouts, the Philippine Commonwealth Army and American units in the Philippines. The Japanese invaded the islands in December 1941, just days after attacking Pearl Harbor and U.S. bases in the Philippines. With little hope of reinforcements, USAFFE forces fought bravely and held off the Japanese for nearly six months, finally surrendering at Corregidor in May 1942.

For the next three years, Filipino guerrillas risked everything to liberate their homeland from the Japanese. Guerrillas sabotaged Japanese military equipment and infrastructure, and targeted Japanese soldiers on patrol with sniper attacks, hit-and-run skirmishes and kidnappings. Spies gathered intelligence and covertly passed it along to American forces. In 1944, as the liberation of the Philippines began, Philippine Commonwealth President Sergio Osmeña and U.S. General Douglas MacArthur issued an order that incorporated guerrillas into the Philippine Commonwealth Army, thus making them official USAFFE soldiers.

Sources: National Archives, World War II Posters 1942-1945

DOCUMENT 2: Filipino Guerrillas with Flag

This photo was taken shortly after the liberation of the Philippines. The original caption reads “US. Flag was hidden for three years in Malsiqui Luzon, Capt. of Pinlae unit with two other Guerrillas.”

Source: U.S. Army Signal Corps Photograph Collection, National Archives, circa 1945.

DOCUMENT 3: U.S. Federal Spending 1940-1945

This table shows federal spending during World War II, adapted from Bureau of Labor statistics. Dollar values in constant 1940 dollars.

| Year | Federal Spending | % Increase | Defense Spending | % Increase |

| 1940 | $9.47 billion | — | $1.66 billion | — |

| 1941 | $13 billion | 37.28% | $6.13 billion | 269.28% |

| 1942 | $30.18 billion | 132.15% | $22.05 billion | 259.71% |

| 1943 | $63.57 billion | 110.64% | $43.98 billion | 99.46% |

| 1944 | $72.62 billion | 14.24% | $62.95 billion | 43.13% |

| 1945 | $72.11 billion | -0.70% | $64.53 billion | 2.51% |

Source: Tassava, Christopher. “The American Economy during World War II”. EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. February 10, 2008. URL http://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-american-economy-during-world-war-ii/

Document 4: “Our New Citizens of the Armed Forces,” 1944

After the U.S. entered World War II, Congress acted to provide for expedited naturalization of noncitizens serving honorably in the military. The Second War Powers Act of 1942 exempted noncitizen service members from naturalization requirements related to race and residence normally in place due to the quota laws of the 1920s. In 1944, Congress also eliminated the requirement for proof of lawful entry to the U.S. Throughout the war, I.N.S. held naturalization services on and near U.S. military bases, including overseas. Here, Henry B. Hazard of the Immigration and Naturalization Service reflects on his time traveling overseas to give servicemembers the oath of citizenship.

In December I returned to the United States after an absence of about ten months. During that period, in my capacity as designated representative of the Commissioner of Immigration and Naturalization, I conferred American citizenship on 3,678 aliens serving with our armed forces who represented 66 countries. In connection with this assignment, it was necessary to travel some 40,000 miles visiting four continents, and crossing and re-crossing both the Arctic Circle and the Equator.

In the past it was necessary that the foreign-born come to this country for permanent residence in order to become United States citizens. Under the exigencies of World War II, however, noncitizens serving honorably in our armed forces are required merely to have been lawfully admitted to the United States. They may have come for only a temporary stay. Furthermore, if in the line of duty they have proceeded beyond the jurisdiction of the courts in continental United States, Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, they are entitled to naturalization on foreign soil under the conditions set forth in section 702 of the Second War Powers Act of 1942.

It is no longer a secret that soldiers and sailors of the United States forces are scattered pretty well throughout many parts of the world. Their exact numbers and locations are, of course, military matters which ought not to be and cannot be revealed, but there are considerable numbers of them distributed about the outposts of North America, the Caribbean area, South America, Iceland, Great Britain, North Africa, Sicily, the mainland of Italy, Egypt, and certain parts of Asia, is a matter of public knowledge. Designated representatives of the Immigration and Naturalization Service chosen by the Commissioner of that Service have performed the naturalization function in the areas described.

…Above all, I shall remember the fine people, men and women—for there were eighteen nurses—on whom I was privileged to confer American citizenship and their very deep appreciation and gratitude at having achieved that goal.

Source: Henry B. Hazard, “Our New Citizens in the Armed Forces Overseas,” in Immigration and Naturalization Service Monthly Review, February 1944 Vol. 1, No. 8.

DOCUMENT 5: GI Bill Posters, circa 1945

Passed unanimously in Congress and signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, better known as the GI Bill, provided tuition, cost-of-living, books and supplies, equipment and counseling services for veterans to continue their education. It provided government-backed loans so returning veterans could purchase homes. The bill also ensured that veterans’ hospitalization needs would be taken care of. Approximately 8 million veterans received educational benefits over the next seven years, costing about $14.5 billion. By 1955, 4.3 million home loans had been granted, with a face value of $33 billion.

Source: National Archives, World War II Posters 1942-1945

DOCUMENT 6: U.S. Federal Spending 1945-1950

This table shows federal spending in the five years after the end of World War II, adapted from Bureau of Labor statistics. Dollar values in constant 1945 dollars.

| Year | Federal Spending | % Increase | Defense Spending | % Increase |

| 1945 |

$92.71 billion |

1.50% |

$82.97 billion |

4.80% |

| 1946 |

$55.23 billion |

-40.40% |

$42.68 billion |

-48.60% |

| 1947 |

$34.5 billion |

-37.50% |

$12.81 billion |

-70% |

| 1948 |

$29.76 billion |

-13.70% |

$9.11 billion |

-28.90% |

| 1949 |

$38.84 billion |

30.50% |

$13.15 billion |

44.40% |

| 1950 |

$42.56 billion |

9.60% |

$13.72 billion |

4.40% |

Source: Tassava, Christopher. “The American Economy during World War II”. EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. February 10, 2008. URL http://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-american-economy-during-world-war-ii/

DOCUMENT 7: Senator Carl Hayden Argues for Cutting Filipino Benefits, 1946

At the end of World War II, after years of high government spending to support the war effort, Congress was looking for ways to trim the U.S. budget. In 1946, a “rescission” bill, to rescind or cut funds that had previously been appropriated, was introduced; if passed, it would cut or save the U.S. about $52 billion. Among the costs that budget-conscious Congressmen, led by Senator Carl Hayden of Arizona, identified were veterans benefits for Filipinos who had served in the U.S. armed forces during the war. An October 1945 report from the Veterans Administration estimated that the lifetime cost of benefits for Filipinos would be about $3.2 billion.

Below are remarks Senator Hayden made to the Senate Appropriations Committee about the reasons why Filipino benefits should be cut.

Because neither the President nor the Congress has declared an end to the war, a [New] Philippine Scout upon separation from service would be entitled to the same benefits as an American soldier who served in time of war. Unless this amendment [to the second Rescission Act] is adopted, a [New Philippine] Scout would be entitled to claim every advantage provided for the G.I. bill of rights such as loans, education, unemployment compensation, hospitalization, domiciliary care and other benefits provided by the laws administered by the Veterans’ Administration. Because hostilities have actually ceased, the amendment makes it perfectly clear that these wartime benefits do not apply and that the 50,000 men now authorized to be enlisted in the [New] Philippine Scouts will be entitled only to pensions resulting from service-connected disability or service-connected death.

…As I see it, the best thing the American government can do is to help the Filipino people to help themselves. Where there was a choice between expenditures for the rehabilitation of the economy of the Philippine Islands and payments in cash to Filipino veterans, I am sure it is better to spend any equal sum of money, for example, on improving the roads and port facilities. What the Filipino veteran needs is steady employment rather than to depend for his living upon a monthly payment sent from the United States.

Source: U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Deficiency, Hearings on H.R. 5604, 79th Cong., 2nd sess., March 25, 1946

DOCUMENT 8: Rescission Act, 1946

At the end of World War II, after years of high government spending to support the war effort, Congress was looking for ways to trim the U.S. budget. In 1946, a “rescission” bill, to rescind or cut funds that had previously been appropriated, was introduced; if passed, it would cut or save the U.S. about $52 billion.

Army of the Philippines, $200,000,000; Provided, That service in the organized military forces of the Government of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, while such forces were in the service of the armed forces of the United States pursuant to the military order of the President of the United States dated July 26, 1941, shall not be deemed to be or to have been service in the military or naval forces of the United States or any component thereof for the purposes of any law of the United States conferring rights, privileges, or benefits upon any person by reason of the service of such person or the service of any other person in the military or naval forces of the united States or any component thereof, except benefits under (1) the National Service Life Insurance Act of 1940, as amended, under contracts heretofore entered into, and (2) laws administered by the Veterans Administration providing for the payment of pensions on account

of service-connected disability or death: Provided, further, That such pensions shall be paid at the rate of one Philippine peso for each dollar authorized to be paid under the laws providing for such pensions.

Source: Rescission Act of 1946, Pub. L. 79-301, H.R. 5158, 60 Stat. 6, enacted 18 February 1946.

DOCUMENT 9: Statement by the President Concerning Provisions in Bill Affecting Philippine Army Veterans, 1946

President Harry S. Truman expressed his dismay over the proposed Rescission Act in these remarks on February 20, 1946. A few days earlier he had signed the bill that stripped Filipino veterans of recognition for having served in the U.S. armed forces.

IN APPROVING H.R. 5158, I wish to take exception to a legislative rider attached to the transfer of a $200,000,000 item for the pay of the Army of the Philippines.

The effect of this rider is to bar Philippine Army veterans from all benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights with the exception of disability and death benefits which are made payable on the basis of one peso for every dollar of eligible benefits. I realize, however, that certain practical difficulties exist in applying the G.I. Bill of Rights to the Philippines.

However, the passage and approval of this legislation do not release the United States from its moral obligation to provide for the heroic Philippine veterans who sacrificed so much for the common cause during the war.

Philippine Army veterans are nationals of the United States and will continue in that status until July 4, 1946. They fought, as American nationals, under the American flag, and under the direction of our military leaders. They fought with gallantry and courage under most difficult conditions during the recent conflict. Their officers were commissioned by us. Their official organization, the Army of the Philippine Commonwealth, was taken into the Armed forces of the United States by executive order of the President of the United States on July 26, 1941. That order has never been revoked or amended.

I consider it a moral obligation of the United States to look after the welfare of Philippine Army veterans.

I recognize, of course, that the Commonwealth Government, and after it, the Government of the Philippine Republic, have obligations to these veterans. But the Government of the Philippines is in no position today, nor will it be for a number of years, to support a large-scale program for the care of its veterans.

However, in recognition of the practical difficulties faced in making payments to Philippine Army veterans under the G.I. Bill of Rights, I have directed the Secretary of War, the Administrator of Veterans’ Affairs, and the United States High Commissioner to the Philippines to prepare for me a plan to meet these difficulties. I have asked that this plan be submitted not later than March fifteenth. I expect to request Congress to make such provisions as are necessary to implement the program when it is evolved.

Source: Truman Presidential Library and Archives

DOCUMENT 10: Philippine Independence Day, 1946

Filipinos struggled for generations to gain national independence. They filed petitions, gave speeches, staged demonstrations, and took up arms. The promise of independence was first made by the U.S. Congress in the Jones Act of 1916. Then followed the ten-year plan set out by the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934. Upon liberating the islands from the Japanese, the Americans and Philippine leaders quickly moved to fulfill the Tydings-McDuffie Act plan, setting July 4, 1946 as the official transition date. At a ceremony at the Luneta, the main square of the capital city of Manila, U.S. officials lowered the Stars and Stripes and raised the flag of the Philippine Republic.

Source: Presidential Library and Museum, Philippines

DOCUMENT 11: Philippines President Osmeña Counts the Cost of Filipino Veterans’ Benefits, 1946

When Filipinos discovered that the Rescission Act denied their service in the U.S. armed forces, they began protesting, carrying signs in front of the U.S. embassy in Manila that read, “Uncle Sam Has Forsaken Us.” Diplomats also lodged formal complaints. Carlos Romulo, the Philippines’ chief diplomat in Washington, D.C. and a veteran himself, eventually rejected the payment appropriated in the act. In this letter to Romulo, Philippines President Sergio Osmeña explained why $200,000,000 was insufficient.

The amount of $200,000,000 appropriated is evidently inadequate for the payment of the benefits it intends to confer. It is at present estimated that approximately 70,000 members of the Philippine Army who were in the active service of the United States died during this war. Assuming that 20,000 of these deceased veterans applied for insurance at $10,000 each, the total amount due their dependents would be $200,000,000. The dependents of the remaining 50,000 with an average insurance of $5,000 each would be entitled to $250,000,000. Aside from these insurance benefits, the bill likewise provides for the payment of pensions for service-connected disability or death. Under the present federal laws, dependents of deceased veterans are entitled to pension or compensation ranging from $50 to $100 a month. Taking an average pension of $65 a month for each dependent of 70,000 deceased veterans, the government would be paying $4,500,000 a month or $49,000,000 a year. Assuming that the average number of years that a dependent is entitled to receive this pension is 15 years, the total amount due for death pension alone would be $735,000,000.

As regards pensions for physical disability, it is estimated that out of the members of the Philippine Army inducted into the service of the United States Army including recognized guerrillas, there are at least 5 per cent who are disabled or approximately 10,000 servicemen whose percentage of disability ranges from 10 to 100 per cent and would therefore be entitled to a monthly compensation of from $11.50 to $115 according to present rates…. With an average disability pension of $50 a month 10,000 soldiers should get $500,000 a month or $6,000,000 a year. Physical disabilities in most cases are permanent and the disabled veteran continues to receive the disability pension during his lifetime. Taking 15 years as the average life of a pensioner, the total sum of $90,000,000 would be due the disabled veterans. Summing up, the amount payable for insurance and pension benefits alone total $1,275,000,000 which is approximately seven times more than the amount appropriated.

…In view of the foregoing considerations, it would be advisable to make every effort to prevent discrimination against Philippine Army soldiers who were ordered into the service of the armed forces of the United States.

Source: “Letter of His Excellency Sergio Osmeña President of the Philippines To Resident Commissioner Carlos P. Romulo instructing him to work for the extension of the full benefits of the G. I. Bill of Rights to Filipino war veterans,” 12 February 1946.

DOCUMENT 12: Cost of Lifetime Benefits to World War II Veterans

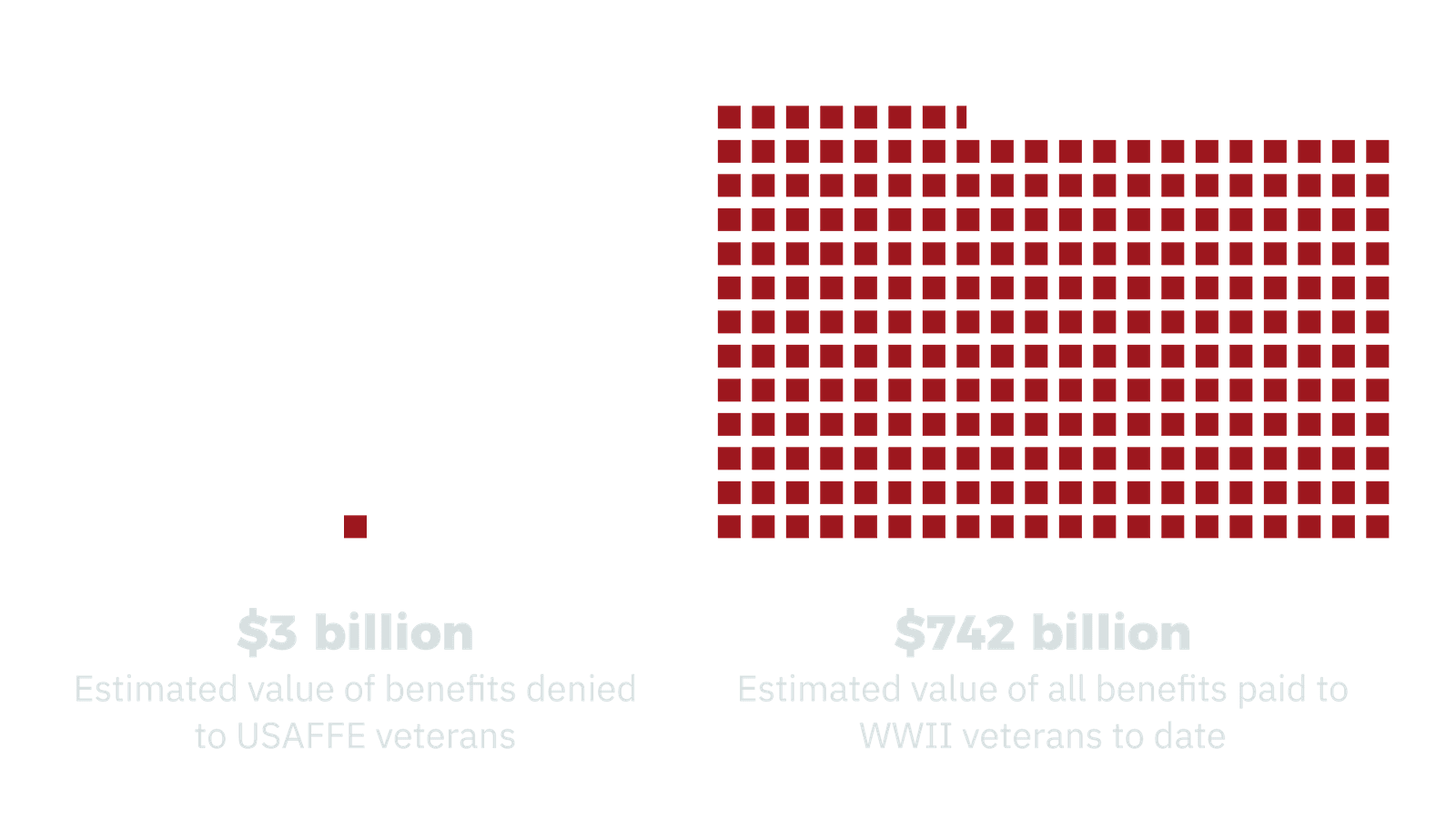

At the behest of Senator Carl Hayden, the Veterans Administration estimated the lifetime cost of benefits for the more than 200,000 Filipino veterans who had served in the U.S. armed forces during World War II. This chart compares that estimated cost, $3.2 billion, to the cost of benefits (pensions, education and home loans, healthcare, etc.) paid to World War II veterans to date.

Source: Ryan D. Edwards, “U.S. War Costs: Two Parts Temporary, One Part Permanent,” Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 113, May 2014.

DOCUMENT 13: Interview with Jon Melegrito, 2019

Jon Melegrito is the son of a Filipino veteran. He and his family moved to the U.S. after the passage of the Immigration Act of 1965. He got involved in a number of activist movements before joining the fight for Filipino veterans’ recognition and benefits. In this oral history interview from 2019, he reflects on what he thinks motivated the U.S. to cut Filipino veterans off from the benefits that other World War II veterans received. This transcript has been slightly edited for clarity. Watch the interview here.

Melegrito: When they received the medal in a ceremony, that was very symbolic and very dignified, their families were of course emotionally relieved in some way. [But] all they really wanted was a thank you. It was not so much the money. You know they weren’t really looking for monetary compensation, even if that certainly would have been helpful. What they really really wanted was an official recognition by the United States government that they served under the U.S. flag. That they exist. That they mattered, that they fought side by side with American soldiers. And yet after the war was over, they were forgotten as if they never existed. Now that was the most painful part for them, for their families, for us.

You know when I think about them now and when I think about my dad, it’s emotionally wrenching. I mean what humiliation, what pain, what bitterness. What else could they possibly do to say I fought in this war. With honor. I served my country with dignity. I sacrifice like everybody else. Why were we singled out? Why were Filipinos singled out among the 66 nations that were part of the allied forces? Filipinos were singled out. To be deprived of their rightful benefits, why? Why were they screwed, right? …Why is America treating them this way? Like we’re still little brown brothers. [Like] we’ll just acquiesce and accept and surrender.

Interviewer: Were you ever able to feel like you had an answer to that question? Why among the one hundred and sixty so other allied nations or those who are fighting alongside the Americans? Why it was Filipinos that never received their rights?

Melegrito: It goes back to being a colonial subject. And when you’re a colonial subject, the colonial master can choose to do whatever it wants to do with you. As I mentioned earlier, “the little brown brother,” has very, very negative connotations. It means I can treat you the way I like to because you’re inferior to me. I don’t have to give you what you deserve. You are less than human. You are second-class citizens. He didn’t deserve to be on the same level as the white soldiers, even if they fought with you under the same flag. Now that’s the root of it. And so long as that is perpetrated, so long as that is the narrative, so long as that’s what drives American policy, that we are little brown brothers and we don’t really deserve these benefits… Because Filipinos were colonial subjects and that’s even if we’re an independent free people now. Somehow they’re still that.

Source: Interview Transcript: Jonathan Melegrito, Duty to Country: Filipino Veterans Recognition and Education Project. Recorded June 2019. https://dutytocountry.org/jonclip

DOCUMENT 14: Congressman Bob Stump Opening Remarks to Veterans Affairs Committee, 1998

Congressman Bob Stump headed the powerful Veterans Affairs Committee in Congress for many years. From this position, he exercised a lot of control over whether or not to appropriate funding for Filipino veterans’ benefits. He steadfastly opposed benefits; these are opening remarks he made from a 1998 hearing on the matter. After this hearing, during which Filipino veterans were once again denied, veterans and activists broke into a spontaneous song, “God Bless America.”

Veterans of the Philippine armed services believe that either President Roosevelt or General MacArthur promised them full U.S. veterans’ benefits. However, we will hear today testimony from the Army historians and the Congressional Research Service who are unable to locate any documentation of such promises.

Members should also understand that this matter is not a simple issue. There are different categories of Filipino veterans, some of who receive full U.S. benefits, but most who don’t….

Many [Filipino veterans] also do not understand what benefits are already available to them in various categories for Filipino veterans.

As a result of our meetings, I corresponded last year with Secretary-Designate Gober requesting that the VA regional offices improve their outreach efforts to veterans of the Philippine armed services to make sure that more of them became informed on what was already available to them.

For fiscal year 1998, the VA estimates payments to veterans of the Philippine armed forces and their survivors will total nearly $55 million. This includes disability compensation, clothing allowance, and dependency and indemnity compensation.

In terms of average annual income in the Philippines and the United States, Filipino veterans are treated better than most U.S. veterans. A Filipino veteran with only a 20 percent service-connected disability receives the equivalent of the average income for citizens of the Philippines. While an American veteran with a 20 percent disability receives compensation amounting to only about 8 percent of the average income. A 100 percent service-connected Filipino veteran receives about 11 times the Philippine annual income.

The Dependency and Indemnity Compensation Program, payments to survivors of Filipino veterans, is $416 a month, or about five times what the average income is in the Philippines.

Much is also made of the presumption that since the Philippines was a territory of the United States at the beginning of World War II, these veterans of the Philippine armed services must have been serving under the U.S. flag and deserve full U.S. veterans’ benefits.

I don’t know how this can be exactly true when the GI Bill, under the veterans’ benefits, was not even established until the 1950’s.

In 1934, the Commonwealth Army of the Philippines was established in preparation for Philippine independence. The Philippine Independence Act of 1934 also gave the President of the United States the authority to call the Philippine National Army into service under U.S. command, but that is not the same as serving in the U.S. Armed Forces. Soldiers of many World War II allied armies served under U.S. command but do not receive any benefit from the VA.

While Filipino forces fought bravely and certainly aided the U.S. in the war effort, in the end they fought for their own and soon to be independent Philippine nation.

It is also worth noting that since the end of World War II, Congress has enacted nearly 20 public laws affecting benefits for veterans of the Philippine armed forces, but had made no major change in the benefit structure now in place. The courts have upheld that basic benefit structure on at least two occasions.

However, Congress has passed provisions over the years to address the differences between economic conditions and living standards in the United States and in the Philippines.

Source: Minutes from meeting of United States House of Representatives Veterans Affairs Committee, Washington, D.C., 22 July 1998. http://commdocs.house.gov/committees/vets/hvr072298.000/hvr072298_0f.htm