Lesson Plan 2:

Confronting U.S. Imperialism in the Philippines

Students watch interview clips with a historian and review primary sources to learn how the U.S. presence shaped life in the Philippines during the colonial era and look for evidence of how Filipinos asserted agency in the face of American dominance. To conclude, students create an illustration depicting the ways American colonization impacted the Philippines.

Summary

Students review six primary sources to learn how U.S. presence shaped life in the Philippines during the colonial period, then create an illustration to synthesize what they learned.

U.S. History, World History | Middle School, High School | 1-2 class periods

Materials

- U.S. Colonization of the Philippines videos

- Primary Source Packet (6 documents)

- Worksheet: “American Colonizers”

Teacher Background

When the U.S. declared war against Spain in 1898, one of the justifications it offered was to liberate Spanish territories, including the Philippines, from Spain’s despotic rule. Filipino nationalists, who longed for an independent Philippine republic, at first hoped that the United States, itself a young republic that had thrown off colonial rule, would support Philippine independence. These hopes soured, though, as it became apparent that the United States intended merely to replace the Spanish as a colonizing power.

As Emiliano Aguinaldo and other Filipino nationalists would make clear, Filipinos were well aware of American history, of the U.S.’s founding documents like the Declaration of Independence, and the traditions of self-government that Americans were so proud of. In their arguments against imperialism, Filipino nationalist drew on this knowledge. Sometimes the tone was appeasing, trying to show that Filipinos were educated and “civilized” enough to self-govern. At other points, the tone of these arguments is derisive and sour, the contrast between the U.S.’s stated beliefs and its actions in the Philippines a source of bitterness and anger.

Throughout history, Americans have looked back to the Revolutionary War as they’ve challenged the government to uphold its ideals. Famously, Abraham Lincoln did so in the Gettysburg Address, arguing that the new nation was founded on a belief in equality, as much as in a belief in liberty; it was this principle, Lincoln argued, that was worth fighting the Civil War over. Suffragists modeled the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments on the Declaration of Independence, and claimed that women had been oppressed by men much the same way the American colonies had been oppressed by King George. Mill girls on strike claimed that as “daughters of free men,” and that bosses’ actions would deny them their independence. Anti-imperialists also drew on American political traditions as they made the case against acquiring the Philippines.

But as the writings of Aguinaldo and other Filipino nationalists demonstrated, people around the world also understood American history and believed in American political ideals. It was heartbreaking for Filipinos and other colonial subjects to discover that the U.S. did not apply principles of liberty, self-government and equality as it emerged on the world stage after 1898.

Grade Level/Subject

Common Core: Middle School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.7 Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.9 Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic.

Common Core: High School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.9 Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

UCLA Public History Initiative | US History Content Standards

- Era 7, Standard 2: The changing role of the United States in world affairs through World War I

UCLA Public History Initiative | World History Content Standards

- Era 7, Standard 5: Patterns of global change in the era of Western military and economic domination, 1800-1914

- Era 8, Standard 5: Major global trends from 1900 to the end of World War II

Teacher Background

Too often, the teaching of the US-Philippines relationship focuses on U.S. interests and policy decisions. While attention is given to pro- and anti-imperialism debates in the U.S., Filipinos’ actions and beliefs are overlooked. This framing replicates the logic of imperialism, denying the agency and interests of Filipinos. This lesson asks students to consider U.S. imperialism from the point of view of Filipinos. Students will trace three phases of the colonial period: 1) a brief hopeful moment when Filipino nationalists declared independence after the Spanish-American War; 2) a brutal war waged by Americans to bring the Philippines in line; and 3) a longer period of “civilian” colonialism, during which Filipinos pressed for increasing control over their own affairs while Americans established political, economic, military, educational and cultural institutions that tied the interests of the two nations together.

Note: this lesson assumes that students are familiar with the Spanish-American War and the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898 by which the U.S. acquired the Philippines.

Instructions

1. Introduction: Confronting the U.S.’s Colonial Past (10 minutes)

Two short videos, totaling about 2 minutes, from the Duty to Country oral history collection to orient students to the question of U.S. imperialism in the Philippines. They are excerpts of an interview with historian Colleen Woods. Play each clip and check for understanding, then ask students to make connections to other aspects of U.S. history.

Check for Understanding and Discussion:

- What reasons does the U.S. use to justify its annexation of the Philippines?

- Why, according to Dr. Woods, has been it difficult for the U.S. to confront its imperial past? Why, according to Dr. Woods, does this matter?

- Dr. Woods introduces the idea of “American exceptionalism.” In your own words, what does this term mean?

- What are other aspects of America’s past that are difficult for present-day Americans to confront? Are these also times when America’s self-image doesn’t match its actions?

2. Review Primary Sources (30-50 minutes)

Tell students that they will learn about the period of American colonial rule in the Philippines, and how Filipinos responded, by going through a set of six primary sources. One half of the class will be looking for examples of U.S. dominance, while the other half will be looking for how Filipinos asserted agency. Divide the class accordingly; we also recommend assigning a note-taker for each group to keep a running list of examples on flip charts or somewhere visible to all students, as well as having students take their own notes.

Go through each of the six documents. After reviewing all six documents, refer back to your earlier discussion about Dr. Woods’ videos. How did the U.S. pursue its interests in the Philippines? Despite the power imbalance, how did Filipinos resist American domination? How did Filipinos attempt to appeal to American ideals about democracy and self-government? Given what they’ve learned, why might Americans find it difficult to confront their imperial past?

An alternate way to structure this part of the activity is to break students into pairs to review documents on their own, with one student focused on how the U.S. exerted influence and the other looking at how Filipinos asserted agency.

3. An American Colony: 15 minutes

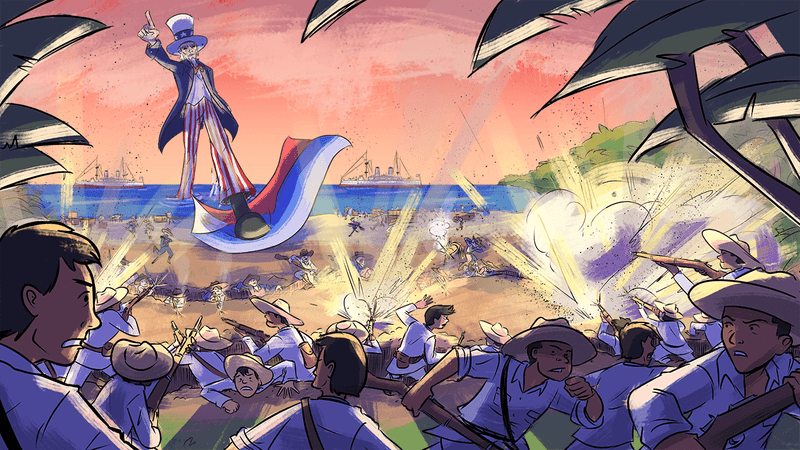

Now that students have reviewed the primary sources, have them look closely at the “American Colony” illustration in Under One Flag and identify symbols and representation of U.S. influence in the Philippines.

Examples include: creation of colonial bureaucracy and Philippine legislature under U.S. purview, establishment of U.S. schools and churches/missions, U.S. recruitment and training of Philippine Scouts, agricultural production and exports to the U.S. Have students connect as many symbols and images in the illustration with references in the primary sources they just reviewed as they can.

Then ask students to describe, in their own words, what impressions or ideas about U.S. colonization in the Philippines the illustration gives. Students might note that this illustration presents colonization as a very orderly system, or how the U.S. imagined its control of the Philippines worked. They might also note that this illustration doesn’t depict the ways Filipinos resisted U.S. imperialism.

4. Illustrate: “American Colonizers” (30-50 minutes)

Now ask students to imagine that the illustration was entitled “American Colonizers” instead of “American Colony.” How would the perspective change if the artist depicted American imperialism in the Philippines from the perspective of Filipinos? What major aspects of life under American rule would need to be illustrated? What images or symbols would an artist use to convey those ideas?

Task students with creating an illustration called “American Colonizers” that depicts the colonial period from the Filipino perspective, drawing on evidence from the historical documents they analyzed and using a similar style to the “American Colony” illustration. Their illustrations should include at least four aspects of life under American rule. Students can use the worksheet to plan their illustrations.

Allow time at the end of the lesson for students to share their work and explain what major ideas they chose to illustrate and what artistic choices they made to do so.

Related Explainers

Primary Source Packet

DOCUMENT 1: Filipinos Declare a Republic, 1899

Filipino revolutionaries had been working to oust the Spanish for more than a decade when the U.S. declared war on Spain in April 1898. Emiliano Aguinaldo, the young charismatic leader of the Filipino nationalists, was hopeful that the Americans would support their struggle for freedom. A month after the decisive American victory over the Spanish navy in Manila Bay, Filipino nationalists declared independence on June 12, 1898. Yet six months later, during the negotiations over the Treaty of Paris, Filipinos were barred from attending or participating in the talks that would determine their own future. Nevertheless, Filipino nationalists adopted a constitution, establishing the first republic in Asia. The photo below is from the inauguration of President Aguinaldo on January 12, 1899.

Source: Fotografico Arias Rodriguez, 1899

DOCUMENT 2: U.S. Troops Pose with Dead Filipino Insurgents and Civilians, 1906

Not long after Filipinos, guided by nationalist Emiliano Aguinaldo, declared an independent republic, an American soldier opened fire on Filipino sentries in February 1899. The next three years brought gruesome war between American and Filipino soldiers, and the devastation of towns, villages, and farms. Violence took the lives not only of some 4,200 U.S. troops and 15,000 Filipino soldiers, but of innocent civilians as well. Historians estimate that at least 100,000 and as many as 300,000 civilians died during or immediately after the war. By any modern definition, the U.S. committed atrocities and war crimes in their savage battle for supremacy in the Philippines, which lasted until 1910 when the last holdouts were defeated. The photograph below shows the bodies of Moro insurgents and civilians killed by U.S. troops during the Battle of Bud Dajo, also known as the Moro Crater Massacre.

Source: National Archives

DOCUMENT 3: A Filipino Peasant Protests the Sugar Industry, 1919

U.S. business interests in the Philippines were twofold: as a market for goods made in the U.S. and a cheap supply of agricultural goods for American consumers. The U.S. wrote a number of tariff laws that favored its own trade prerogatives. Elite landowning Filipinos accommodated U.S. interests, but the majority of Filipinos received little benefit. Labor in sugarcane fields was backbreaking. And, as sugar production grew, it left less acreage and fewer man hours for Filipinos to grow food for themselves. In 1919, Antonio Villanueva, a peasant in the Negros Islands sugar-growing region, wrote this letter on behalf of himself and his neighbors, to the Director of Lands, an American colonial administrator in Manila.

Sir, to inform you that we are poor and that we can be smashed, as most rich and influential people believe, I state herewith that my neighbors and I do not own even a spot of land here in the Philippines, except this land where we are now working.

As to their information that they would cultivate the land for sugar cane, we do not care what crops they will plant in other portions of the lot (No. 998), provided that the claimants will not include the parts we occupy. We being poor who do not have capital like they have, do not propose to do more than to produce food stuffs that can help to maintain our living. They, being rich who have money to buy private lands at any time they want, if they have conscience and mercy on us, should leave us the portions we occupy and they can continue working on the portions that do not belong to us.

To mention the fact how hard it is in the life of a poor man to improve a piece of land, by planting bamboo, bananas and food crops, I wish you could imagine him, working either under sunshine or under rain; with iron bar to dig holes in the ground; with hoe to pulverize the soil oftentime bathed with sweat from head to heel.

The claimants informed that they would pay us the improvements we have made. They can say and do that but what about us? Where will then be our home sweet home? It is natural for human being, from childhood to manhood, that he loves more the things that he owns than those which are just loaned to him. In short I should say it will be more advantageous to have real Philippine Native Citizens . . . [as] owners than few rich influential land owners who usually keep the poor under miseries.

…There is a common saying here that “influence works wonder”. We hope, however, that for our case, you would exert all our influence to save us from the threatening injustices and oppressions of the mighty. This is to say that the land we have been occupying since the Spanish time and lived faithfully therein will likely be taken by the mighty persons in a minute. We hope that these merciless rich people who are proud because they are influential and who think that they could easily rob the rights of the poor and non-influential ones be given a lesson by teaching them squarely by the power of the law which your office has in store for the poor. Negros [a region in the Philippines] in particular and the Philippines at large will never attain its highest development of prosperity if we the poor that make the mass or the greater part of the population will always be allowed to be oppressed by the rich and influence of richness and high offices.

… Since the policy of our Government is to distribute land equally as far as possible among her Citizens, I therefore hope that you will not tolerate that our land be taken from us by influential men who have no right at all to do so…

Equality among men is the safest foundation of Democracy. Trusting for your immediate action on the matter, I beg to remain,

Very respectfully,

Antonio Villanueva

[His thumb mark]

Source: Quezon Papers, National Library of the Philippines, Manila; reproduced in Larkin, John A. Sugar and the Origins of Modern Philippine Society. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

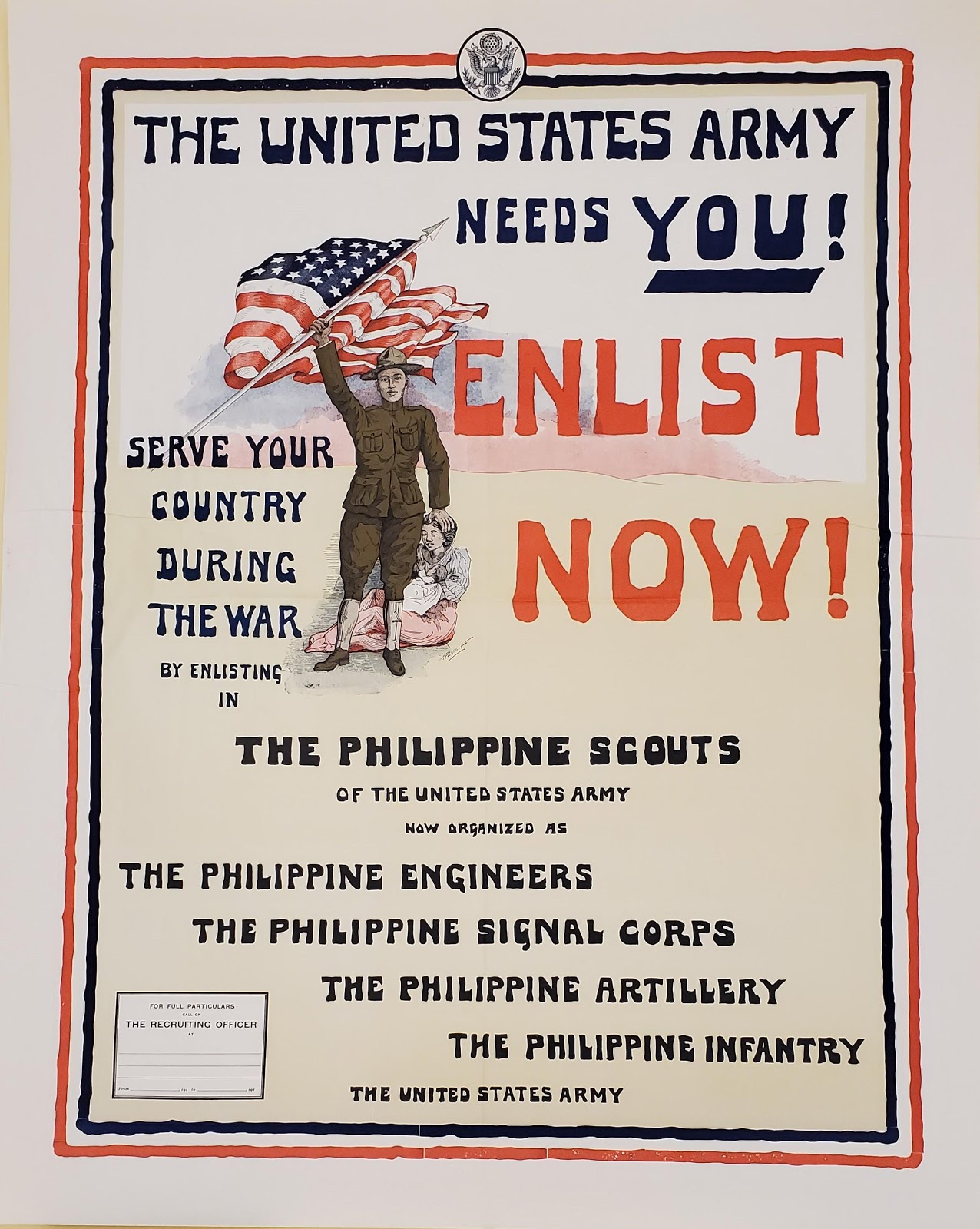

DOCUMENT 4: Philippine Scouts Recruiting Poster, circa 1918

In the Philippines, the United States established military and naval bases near Manila, on the fortified island of Corregidor, and throughout the archipelago. The U.S. Army recruited Filipinos directly into its ranks in a new force, the Philippine Scouts. By the 1920s, the Scouts outnumbered regular Army soldiers in the Philippines. They were some of the best-trained and most devoted soldiers in the U.S. forces. By law, they were soldiers in the United States Army, but they were paid half what American soldiers earned, and most were barred by law from becoming officers.

Source: Massachusetts Historical Society, circa 1918

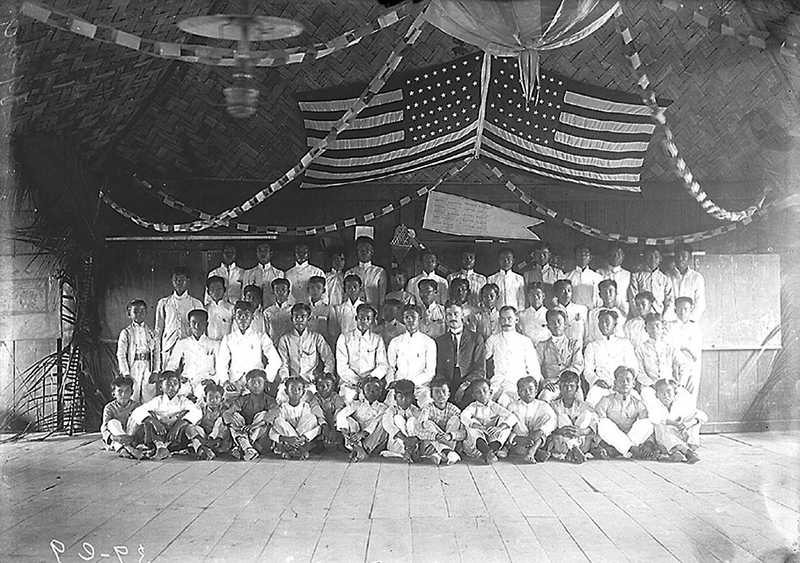

DOCUMENT 5: Schools for Filipinos, 1905 and 1914

Americans claimed that it was colonizing the Philippines in order to “civilize” them. To fulfill this dubious promise, American missionaries and educators flooded the islands, establishing schools, hospitals and other modernizing institutions. Thousands of teachers arrived from the U.S. to teach English, American civics and other subjects. Some Filipino students were selected to study in the U.S., with the expectation that they would return to the islands and help run the colonial bureaucracy or become teachers themselves.

American schools, like the one below on the island of Isabela, taught English, celebrated American holidays like the Fourth of July, and decorated with American flags and portraits of George Washington and other American leaders. Just a few years before this photo was taken, Americans outlawed the display of the Filipino flag and the celebration of Philippine national holidays.

A school in the Philippines, 1905

Graduates from a nursing school established by Episcopalian missionaries in Quezon, 1914

The first modern nursing school in the Philippines was established in 1906, following Baptist missionaries’ realization that they would need more local help to staff their medical clinics and hospitals. Dozens of other Christian missionaries followed suit, establishing nursing schools throughout the islands.

Sources: Top: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology. Bottom: NurseLabs.com, History of Nursing in the Philippines.

DOCUMENT 6: Manuel Quezon Reports that Filipinos Are Ready for Independence, 1919

After 1903, the U.S. colonial presence in the Philippines shifted from a military occupation to a civilian colonization. Americans set up a bureaucracy to administer their colonial possession. Filipino lawmakers and diplomats, usually from elite backgrounds, performed a delicate dance of trying to persuade U.S. leaders that Filipinos were ready for independence without alienating their powerful overlords. Here, Manuel Quezon, former envoy to Washington and a senator in the territorial legislature, attempts to convince Americans that Filipinos have earned the right to self-rule. He references the Jones Act of 1916, which promised the Philippines would someday be independent but left the process vague and the decision of when to begin up to the United States. In 1919, responding to President Woodrow Wilson’s call for self-determination for all nations in his 14 Points speech delivered at the Paris Peace Conference, many nationalist leaders were stepping up their calls for independence from European colonial powers.

The Filipino people feel that the time has come when steps should be taken immediately by the Government of the United States for the recognition of the sovereignty of the Filipino people over their own country. It is, I think, the first time in the history of the world where a country under the sovereignty of another seeks its separation from the latter not on the ground of grievances or abuses that call for redress but rather on the ground that the work of the ruling country has been so well and nobly performed that it is no longer necessary that she should still direct the destinies of her colony; and so the colony, with love and gratitude for the governing country, seeks her separation….

We have kept order and peace during these three years of [World War I]. We have not only done that, we have not only kept peace and order within our borders, but we were ready—nay, anxious—once you had entered the war yourselves, to go outside of the Philippines and fight with you and for you in the battle fields of France, or wherever the Government of the United States would care to send our men. The Filipinos have shown in this critical time their loyalty to the United States, their appreciation of what you have done for them and have shown it not in words but in deeds….

The Filipinos have organized, as I said, a new government. Under this new government the country has made progress in education, in commerce, in industry, in agriculture. In other words, it has made progress in every way. So we feel that the conditions laid down by the Jones Act as prerequisite for the granting of Philippine independence have been performed; that we have shown not only that a stable government can be established in the islands but that there is now one there.

There is still another reason why we think that the independence of the Philippines should be granted at this time and that is because of the attitude taken by this Government in the recent war. You said you have gone to war for the liberation of mankind; for the right of every people to govern themselves. Indeed, you have made good those declarations in thus far recognizing the independent existence of several countries of Europe; certainly it would be nothing but natural that the Filipinos should feel that you would make those declarations good with regard to the people of the Philippines. You have recognized the independence of countries of Europe which have been under the control of autocratic powers; who have had no opportunity of exercising the powers of self-government, and to these countries you were not pledged to give independence, you were not in any way related, you were not tied by bonds of long association and affection. How can you afford not to recognize the independence of the Filipino people whom you have solemnly promised independence, whom you have helped to acquire the science and practice of self-government, and who are bound to you by ties of affection, friendship, and eternal gratitude? The granting of our national freedom will be at this time the object lesson that you could give to the world that this country can give of her belief in democracy and in the rights of every people to be free and to govern themselves.

Source: Manuel Quezon, “Statement of Hon. Manuel L. Quezon, President of the Philippine Senate and Chairman of the Philippine Mission,” in Philippine Independence: Hearings before the Committee on the Philippines, United States Senate, and the Committee on Insular Affairs, House of Representatives, Held Jointly (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919), 4-8.

American Colonizers: Planning Worksheet

Directions: Create an illustration of the colonial period in the Philippines from the Filipino perspective, inspired by the illustration “American Colony.”

Your illustration should include at least four aspects of life in the Philippines during the period of U.S. colonization. (It can include more than four.) As you decide what to include, consider political, economic, social, cultural, and military life in the Philippines during the colonial period.

Use the chart below to plan the ideas and symbols you’ll use in your illustration.

| Aspect of Life in Philippines Under U.S. Control | Why It’s Important to Include | Symbol or Image |