Explainer 13:

The Rescission Act and the G.I. Bill

Students compare and contrast two post-war bills that drastically differed in their effects on World War II veterans.

Teacher Background

At the heart of the Filipino veterans story is the Rescission Act, a 1946 law that stripped Filipino veterans of all benefits earned by their service in the U.S. military during World War II. The Rescission Act exemplifies the Duty to Country theme of “promises made, promises broken.”

If you do nothing else to teach this history, introduce the Rescission Act to your students. Most U.S. history survey courses include a lesson or two about demilitarization at the end of World War II and the transition from the sacrifices of wartime to the post-war economic boom. Students learn about the G.I. Bill, typically considering its purpose, the benefits it conferred, the social and economic effects it caused, and the degree to which non-white veterans were able to take advantage of it. This is a natural point to introduce the Rescission Act, comparing and contrasting these two major laws concerning World War II veterans.

This explainer introduces both laws and suggests different ways to lead students through a comparison and analysis of the laws, depending on the time you have available. While the larger story of U.S. imperialism in the Philippines, the war, Filipino immigration to the U.S., and the veterans’ social justice movement for recognition and benefits is complex, it takes only 10-15 minutes to add the Rescission Act and introduce students to the important but forgotten story of Filipino veterans.

Throughout American history, the idea that the government has a special responsibility to care for its veterans has been a powerful ideal and rallying cry. Concerns about the Continental Congress’s ability to deliver its promised pensions roiled Revolutionary War armies. Over the course of the 19th century, the federal government and states evolved a system of pensions, hospitals and homes for elderly poor and disabled veterans. After World War I, in the midst of the Great Depression, Great War veterans staged the first march on Washington to demand their promised bonuses; the Veterans Administration was finally established in 1930.

Passed unanimously in Congress and signed by FDR in 1944, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, better known as the GI Bill, provided tuition, cost-of-living, books and supplies, equipment and counseling services for veterans to continue their education. It provided government-backed loans so returning veterans could purchase homes. The bill also ensured that veterans’ hospitalization needs would be taken care of. Approximately 8 million veterans received educational benefits over the next seven years, costing about $14.5 billion. By 1955, 4.3 million home loans had been granted, with a face value of $33 billion. The bill also appropriated half a billion dollars for the construction of new veteran hospitals. The long-term economic impact of this bill is in the trillions of dollars, as home values increased over time and became a source of generational wealth to pass onto children and grandchildren, veterans used their college degrees to move up the economic ladder into the middle class, and other ripple effects.

Compare that to the Filipino veterans’ situation. At the end of World War II, after years of high government spending to support the war effort, Congress was looking for ways to trim the U.S. budget. In 1946, a “rescission” bill, to rescind or cut funds that had previously been appropriated, was introduced; if passed, it would cut or save the U.S. about $52 billion. Among the costs that budget-conscious Congressmen identified were veterans benefits for Filipinos who had served in the U.S. armed forces during the war. An October 1945 report from the Veterans Administration estimated that the lifetime cost of benefits for Filipinos would be about $3.2 billion.

At the same time, the U.S. was set to fulfill the promise of the Tydings-McDuffie Act and finally grant independence to the Philippines. In a solemn ceremony on July 4, 1946, the U.S. flag was lowered and the Philippine Republic’s flag was raised in Manila’s main square. Despite wartime orders from President Roosevelt and General MacArthur making clear that Filipinos who fought for the U.S. were full members of the U.S. armed forces, members of Congress argued that the Philippines now had responsibility for caring for Filipino veterans. To help them do so, Congress added a rider to the rescission bill. It provided a one-time $200 million-dollar payment to the Philippines government to help them provide veterans care. It also stated that Filipinos who served in the U.S. military during the war would henceforth not be considered veterans, and therefore not entitled to any veterans benefits from the United States government.

The confluence of these two events, post-war cost-cutting measures and the declaration of an independent Philippines, was disastrous for Filipino veterans. The 1946 Rescission Act declared that they alone, of all people who had served in the U.S. military during World War II, would be denied veterans benefits.

Suggested Teaching Strategies

- Introduce the G.I. Bill and the Rescission Act or have students look up and define each. This Explainer includes primary sources to help students understand the laws, but you can rely on secondary sources and direct teacher instruction depending on time and the level of your students.

- The text of the Rescission Act itself, provided here, is difficult to parse, so it may be simpler for the teacher to highlight a few key bullet points in his/her own words.

- If using the primary source, ask students to underline the key phrase the cuts Filipino veterans benefits (“shall not be deemed to be or to have been service in the military or naval forces of the United States…for the purposes of any law of the United States conferring rights, privileges, or benefits upon any person by reason of the service of such person”).

- Have students create a chart comparing the two laws, listing their purpose, effects, and costs. Alternatively, you could have students create a Venn Diagram to compare and contrast, with the central feature being that both were laws concerning World War II veterans’ benefits.

- Ask students to consider the rationale provided by Congress for the Rescission Act (that it would save money, that the U.S. didn’t owe benefits to Filipinos now that the Philippines were an independent country). Questions to probe include:

- Is this reasoning justified?

- How does the projected cost of Filipino veterans’ benefits compare to the costs of the G.I. Bill?

- What role might race have played in this decision? What other examples of anti-Asian bias in U.S. laws from around the same time put the Rescission Act in context (immigration quota laws, Japanese internment, red lining, etc.)?

- How did the Rescission Act affect Filipino veterans’ ability to immigrate to the United States?

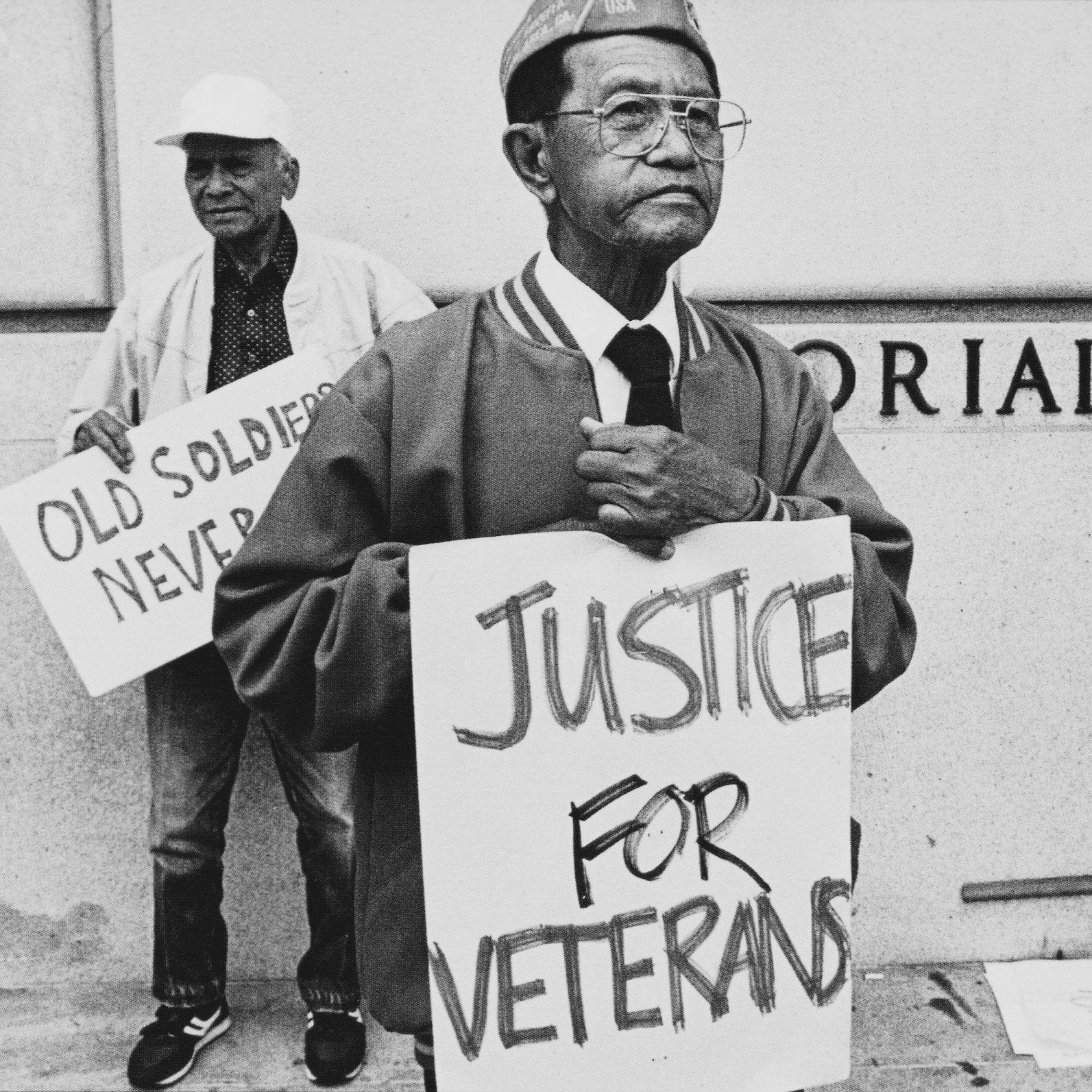

- Before concluding your mini-lesson on the Rescission Act, note that Filipino veterans protested the bill for more than 70 years, including through lawsuits, petitions to Congress, and acts of civil disobedience. In 2009, a small amount of money was appropriated to provide one-time payments to surviving veterans, and in 2016, Congress awarded all Filipino veterans the Congressional Gold Medal in honor of their service.

| G.I. Bill | Rescission Act | |

| Date passed | 1944 | 1946 |

| Purpose | To provide benefits to veterans of World War II, including home loans, educational loans, and access to medical care | To save the U.S. government money at the end of World War II |

| Effects |

|

|

| Who was affected |

|

|

| Cost |

|

|

Curriculum Standards

Common Core: Middle School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

Common Core: High School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

GI Bill Posters, circa 1945

The GI Bill was passed by Congress in 1944. It provided tuition and counseling services for World War II veterans to go to college. It also provided loans so veterans could purchase homes. It provided free medical care to veterans through Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals.

Source: National Archives, World War II Posters 1942-1945

Rescission Act, 1946

At the end of World War II, Congress was looking for ways to trim the U.S. budget. In 1946, a “rescission” bill, to rescind or cut funds that had previously been approved, was introduced. If passed, it would save the U.S. government about $52 billion total. One section concerned Filipino veterans; it offered $200,000,000 as a one-time payment to provide small pensions but excluded them from any other veterans benefits.

Army of the Philippines, $200,000,000; Provided, That service in the organized military forces of the Government of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, while such forces were in the service of the armed forces of the United States pursuant to the military order of the President of the United States dated July 26, 1941, shall not be deemed to be or to have been service in the military or naval forces of the United States or any component thereof for the purposes of any law of the United States conferring rights, privileges, or benefits upon any person by reason of the service of such person or the service of any other person in the military or naval forces of the united States or any component thereof, except benefits under (1) the National Service Life Insurance Act of 1940, as amended, under contracts heretofore entered into, and (2) laws administered by the Veterans Administration providing for the payment of pensions on account of service-connected disability or death: Provided, further, That such pensions shall be paid at the rate of one Philippine peso for each dollar authorized to be paid under the laws providing for such pensions.

Source: Rescission Act of 1946, Pub. L. 79-301, H.R. 5158, 60 Stat. 6, enacted 18 February 1946.