Lesson Plan 5:

You Decide: Filipino Veterans’ Long Fight for Justice

In this lesson, students debate what to do at each of five key turning points in the long fight for veterans’ benefits and recognition. They learn about the different strategies activists employed, discover how they responded to setbacks, and consider how citizens can hold their government accountable.

Summary

Students read scenarios and debate what to do at each of five key turning points in the long civil rights movement for Filipino veterans’ benefits and recognition.

U.S. History, Asian American Studies, Civics/Government | Middle School, High School | 1 class period

Materials

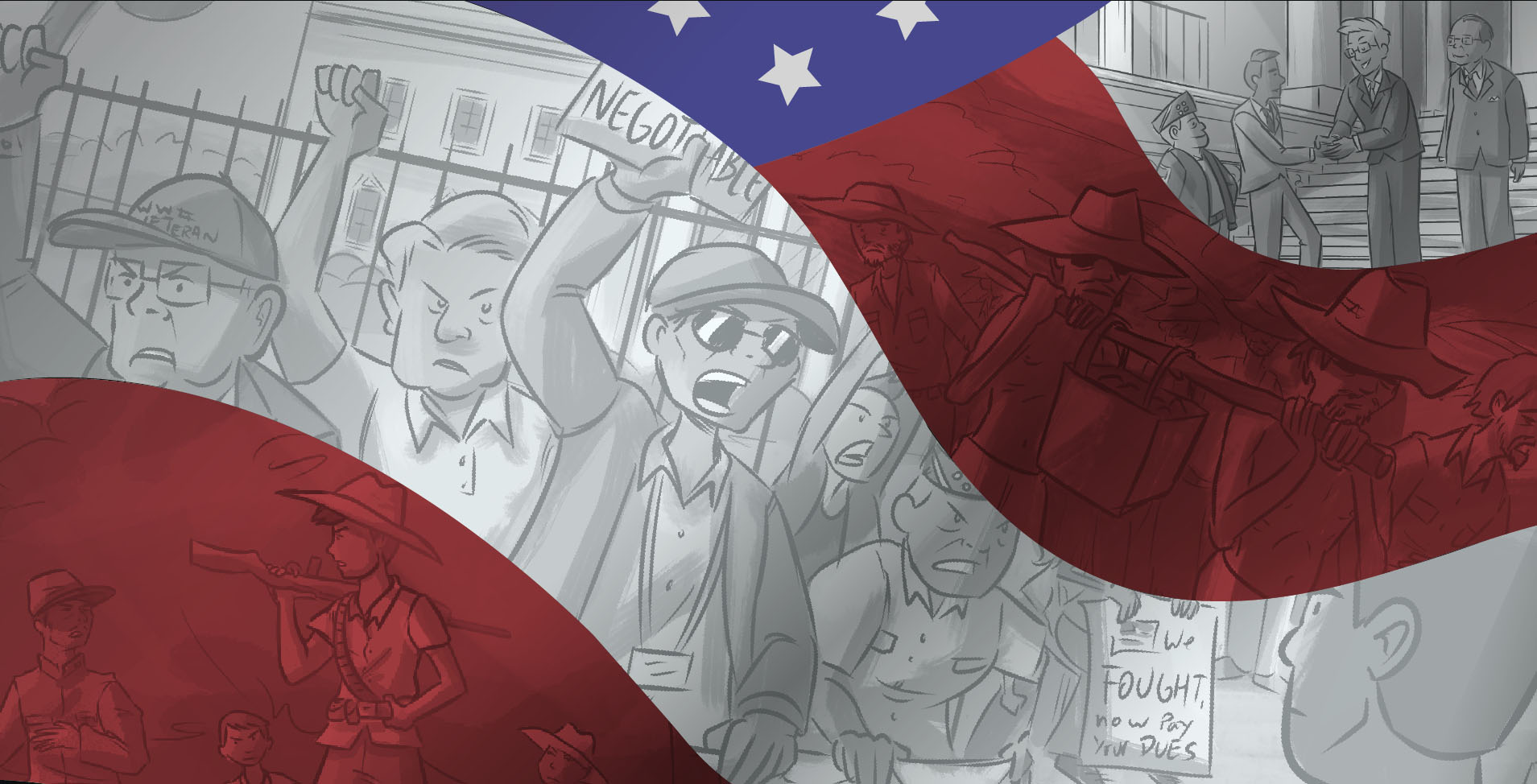

- Greatest Generation illustration

- Scenario cards (each student should have a copy of each scenario)

Grade Level/Subject

Common Core: Middle School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

Common Core: High School

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

UCLA Public History Initiative | US History Content Standards

- Era 9, Standard 4: The struggle for racial and gender equality and the extension of civil liberties

- Era 10, Standard 1: Recent developments in foreign and domestic policies

Instructions

1. Introduction (5 minutes): Greatest Generation

Display the “Greatest Generation” illustration from the exhibit Under One Flag. Ask students to describe what’s going on in the illustration: who’s taking action, where are events happening, and what are the people asking for? Students should identify that these are scenes of activists in the long struggle for Filipino veterans benefits. In today’s lesson, students will learn the real story behind these scenes.

2. Role Play (40-50 minutes)

Break students into groups of 3-4. Pass out the first scenario about the Rescission Act. Allow students time to read the scenario, then to debate the options on the card (about 10 minutes each). Students must decide what to do, whether by selecting one of the options presented or designing their own response. Ask each group to share out what choice they made and why. Then reveal what actually happened before introducing the next scenario. Repeat until all scenarios have been debated.

a. 1946: The Rescission Act | What Really Happens: The Philippines reject the offer; diplomat Carlos P. Romulo, himself a veteran, testifies before the U.S. Congress in 1948, saying: “The Rescission Act deprives Filipino veterans of veterans’ benefits, with the proviso that $200 million be appropriated to the Army of the Philippines. These $200 million, which are purportedly in lieu of the benefits of which Filipino veterans were thus deprived, are actually not even sufficient to cover their back pay. The Philippine Government has chosen not to accept the appropriation.”

b. 1960s-1970s: The Courts | What Really Happens: Filipino veterans try all three strategies, bringing court cases throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Sometimes they even convince judges that the U.S.’s denial of their claims is unjust, but whether in the initial decision or on appeal, judges find against the veterans. The Rescission Act is clear; as long as it remains on the books, veterans don’t have a case.

c. 1980s: Change the Law | What Really Happens: Filipino veterans and their advocates tried all of these strategies, often at the same time. Senator Inouye introduced a bill every year for 18 years to repeal the Rescission Act. DC-based veterans were a regular sight in the halls of Congress. Activists like Jon Melegrito started working with college students at George Washington University to teach them the history and get them engaged in the fight. Nearly every Filipino American community organization was involved in some way. But Congress only met the activists half way: the Immigration Act of 1990 included a provision that allowed for the naturalization of Filipino veterans without providing for benefits or overturning the Rescission Act.

d. Immigration Act of 1990 | What Really Happens: About 25,000 veterans applied for U.S. citizenship, and of these, about 17,000 moved to the U.S. Many had a hard time making ends meet without pensions, though, and lived in poverty. Activists kept up their fight for full benefits, while Senator Inouye introduced a bill every year to repeal the Rescission Act.

e. 1990s: Getting Confrontational | What Really Happens: The fight enters its most confrontational phase, with veterans and their allies participating in all kinds of civil disobedience. Several powerful new groups are formed, They stage a “Bataan Death March” in Washington, D.C. They do sit-ins in V.A. offices. Protestors set up an encampment in L.A.’s MacArthur Park and chain themselves to the gates of the White House in Washington, D.C. After attending a hearing of the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, during which their benefits are again denied, they break out into a spontaneous chorus of “God Bless America.” They win limited health and burial benefits, but that’s about it until 2009. Then, Senator Inouye manages to insert a Filipino Veterans Equity Compensation Fund (FVEC) into the 2009 stimulus bill passed by President Barack Obama. Soon afterward, Congress allocated $198 million to the fund and awarded payments of $15,000 for eligible Filipino veterans who were U.S. citizens. It provided $9,000 for Filipino veterans who were Philippine citizens. About 48,000 veterans navigated the complicated process to obtain these benefits before time expired. The law also recognized that service in USAFFE was, indeed service “in” the U.S. armed forces. In 2016, advocates also obtained a Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian honor, in recognition of Filipino veterans’ service. To this day, the Rescission Act has never been repealed.

3. Discussion (5-10 minutes)

Ask students to reflect on the long activist movement for justice and equity for Filipino veterans; a few questions for discussion are below:

- Are you surprised that it took so long to get any sort of change or recognition? Why or why not?

- Why do you think it was so difficult to obtain benefits for Filipino veterans? What, if anything, had changed by 2009 that the U.S. finally relented and provided some monetary benefits to veterans?

- What did it feel like to accept “half a loaf” or to see a strategy get nowhere with the powers that be? What do you think kept activists going in spite of setbacks and defeats?

- What have you learned about activism and the role of citizens in making change in a democracy?

- Would you say that justice has been achieved? If not, what, if anything, can be done at this point to honor Filipino veterans and hold the U.S. to its promises and ideals?

4. Assessment

Have students select another long civil rights struggle in U.S. history (the women’s suffrage movement, one of the antebellum reform movements, the Hawaii sovereignty movement, etc.) and to compare and contrast the progress of the movement with that of Filipino veterans. Points of comparison and contrast should include strategies and tactics, what setbacks each movement faced and how groups moved forward despite them. In his oral history, Jon Melegrito discusses the specific ways Filipino veteran activists looked to the U.S. civil rights movement and you may want to have students watch some or all of it to begin this exercise (see especially 7:57, 12:50-15:10 timestamps).

Related Explainers

Scenario Cards

Scenario 1: The Rescission Act

It’s 1946. The final months of World War II, after the Americans gained a foothold on the island of Leyte in October 1944 and began to retake the archipelago, were brutal. The Americans waged a heavy bombardment of cities and Japanese military installations; in Manila alone, more than 100,000 civilians were killed. The retreating Japanese commit atrocities. But Filipino guerrillas emerge from the jungles to aid American forces and, on September 2, 1945, the Japanese surrender. In all, 200,000 Filipinos have served in the United States Armed Forces of the Far East (USAFFE), risking everything for the liberation of their homeland.

The end of the war also means, at long last, the dream of a free and independent Philippine republic is at hand. The Americans have kept their promise to grant independence. At a ceremony at the Luneta, the main square of the capital city of Manila, U.S. officials lower the Stars and Stripes and raise the flag of the Philippine Republic. Manuel Roxas takes power as the first President of the new republic.

But though the Philippines are now independent, they maintain strong ties to the United States. The Philippines are key to the U.S.’s strategic interests in the region and are negotiating a Military Bases Agreement that will result in the U.S. having 23 bases in the country, including huge facilities for the navy at Subic Bay and the air force at Clark Air Base. The U.S. is training, providing equipment and giving financial support—$200,000,000—to the newly formed Armed Forces of the Philippines. In the final negotiations for independence, the U.S. also inserts a number of trade regulations and other legal measures that tie the Philippine economy to American interests.

And Filipinos have family ties to the United States; many have family members who immigrated to the mainland during the colonial period whom they would like to join. But the transition to independence means that Filipinos are now subject to the U.S.’s strict immigration quotas, which limit visas for Filipinos to just 100/year.

During the war, Filipinos and Americans had fought under one flag. A series of wartime orders had declared that Philippine Scouts, members of the Philippine Commonwealth Army and guerrillas were all full-fledged members of the U.S. military. That means that they are owed benefits, including pensions and healthcare, as well as, per the terms of the 1940 Nationality Act, the right to naturalize as U.S. citizens. But Filipinos who want to immigrate find that all of the Immigration and Naturalization Services offices are mysteriously closed in the Philippines, and no American immigration officials can be found.

The Americans approach Philippine diplomats with an offer. The U.S. Congress has passed a law, the Rescission Act, to cut government spending. After years of high budgets during the war, the U.S. says it’s necessary to find savings and the estimated $3.2 billion lifetime cost of veterans for Filipinos, it’s decided, is too high. Besides, the Americans say, the Philippines is independent now; taking care of Filipino veterans is the job of the Philippine government, not the U.S.

It’s clear that American leaders, taking cues from the American public, are ready to put the war years behind them. This includes their former colonial subjects and comrades-in-arms in the Philippines. The Rescission Act includes specific language that cuts Filipino veterans off from any claim of benefits. But it includes a provision: $200,000,000 to the Philippine government to care for USAFFE veterans.

Imagine you’re a Philippine diplomat in 1946. You have to decide whether to take the $200,000,000 from the Americans. The Americans are your biggest ally and strong ties exist between your two nations. There are 200,000 Filipino veterans; without the Americans’ money, it’s not certain your young country, emerging from a devastating war, is in any position to set up hospitals, provide healthcare or pay pensions to veterans and widows.

What do you do?

- Accept the offer. $200,000,000 may not be enough to cover the full cost of pensions and care, but it’s better than nothing. Besides, it’s important to stay on good terms with your biggest ally.

- Reject the offer. After all the sacrifices of the war years and meeting all of the U.S.’s many terms for independence, this offer is insulting. Filipino veterans are owed those benefits, and the U.S. has a moral obligation to live up to its promises and values. Besides, if we accept this money now, it may be harder to ask for more in the future.

- Something else. (In your group, propose an alternative solution.)

Scenario 2: The Courts

The United States has broken its promise.

The U.S. has washed its hands of the more than 200,000 Filipino veterans who served under the U.S. flag during World War II. The 1946 Rescission Act has declared that Filipinos veterans aren’t eligible for any veterans benefits, including healthcare and pensions, from the U.S. government. Filipino veterans can’t naturalize as U.S. citizens either, even though the 1940 Nationality Act stated that those who served in the U.S. armed forces could do so, and more than a hundred thousand servicemembers from more than 60 countries have become U.S. citizens thanks to their wartime service.

Veterans are devastated. Healthcare and pensions mean the opportunity to build lives and families after the devastating war years. Some of them want to immigrate to the U.S., either to take advantage of the booming post-war American economy or to reunite with loved ones who immigrated during the colonial era. Philippine diplomats register their dissatisfaction with the Americans, rejecting the Rescission Act’s appropriation of $200 million from the U.S. government to care for veterans. Protestors march in front of the U.S. embassy in Manila, carrying signs that say “Uncle Sam Has Forsaken Us.”

A small breakthrough occurs in 1966, when the U.S. agrees to transfer wartime backpay (wages, not pensions or healthcare costs) to the Philippine government; most of those funds never make it to veterans. It’s been more than 20 years and Filipino veterans haven’t gotten anywhere through diplomacy. The Rescission Act remains on the books, and so long as it does, Filipino veterans will be denied benefits.

It’s time for a new strategy. It’s the 1960s. Civil rights activists in the United States have had a lot of success changing U.S. law by bringing court cases and getting judges to strike down discriminatory laws. And, unlike earlier, there is now a growing population of Filipino-Americans. The 1965 Immigration Act has enabled Filipinos to immigrate to the U.S., and thousands do so (in time, the second-largest Asian immigrant group to the U.S. will be Filipinos). Among these are veterans. When they become citizens, they’re entitled to bring suit in U.S. courts.

But to bring a claim in the U.S. courts, you have to point to a specific instance of wrongdoing, then methodically prove your case by bringing evidence and arguing persuasively. Maybe a veteran in the U.S. could test the waters by going to the Veterans Administration and claiming veterans; if rejected, he could sue.

Then again, there’s the fact that after the war but before Philippine independence, all U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) offices mysteriously closed throughout the islands. This meant that Filipinos who could have used this narrow window to begin the naturalization process before naturalization couldn’t do so. That seems like a pretty clear-cut example of U.S. wrongdoing.

And there’s also the fact that Filipinos were alone, among World War II servicemembers 66 nations, had their wartime service deemed ineligible for benefits; isn’t that discrimination against Filipinos? There are a lot of U.S. laws that bar racial discrimination, including the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The legal underpinnings of the civil rights movement’s victories rested on the “equal protection” principle. Maybe Filipinos can convince a judge this way.

You’re a lawyer for Filipino veterans seeking benefits. Which case do you think you can prove in court?

- Have your client, a U.S. citizen, attempt to claim benefits and, if the V.A. rejects, go to court and prove your client’s wartime service. Make a claim that he, like any other World War II veteran, is owed veterans benefits.

- Show that the U.S. broke its own laws by closing I.N.S. offices in the Philippines between the end of the war and the declaration of Philippine independence in July 1946. Offices should have been open, veterans who wanted to should have been able to start the naturalization process, and the U.S. was clearly trying to dodge its responsibilities by making it impossible to find an immigration official.

- Bring suit under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The U.S. has a long history of racial discrimination, especially when it comes to immigration and Asian Americans. Also, recently, the U.S. courts have been very favorable to racial minorities and women who’ve brought forth discrimination cases.

- Avoid the courts. It’s going to be difficult to prove that veterans are owed any rights so long as the Rescission Act remains on the books. Focus your efforts on repealing the law, rather than trying to have it struck down.

- Something else. (In your group, propose an alternative solution.)

Scenario 3:Congress

The courts are a dead end. For more than 20 years, Filipino veterans have been suing the U.S. government—the Veterans Administration, the Immigration and Naturalization Services—over the denial of their benefits. Every time, even with sympathetic judges, they run into the fact that the 1946 Rescission Act remains the law of the land, and it clearly states that Filipino veterans are not owed any benefits from the U.S. government. Veterans are getting older; it’s been 40 years since the war ended and the fight for benefits and recognition began. By 1988, when the U.S. Supreme Court finds against veterans in INS vs. Pangilinan, activists know it’s time to change course.

But some interesting things have changed in the meantime. Following the passage of the Immigration Act of 1965, the Filipino American community has grown exponentially. Now there are members of Congress working for the interests of this constituency. Younger Filipino Americans, the children and grandchildren of veterans, are engaged in the fight. The civil rights movement of the 1960s and the wave of post-1965 immigration have contributed to an Asian American identity, with Asian Americans from different nationalities (Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, Vietnamese, etc.) seeking and finding solidarity with each other. Many of Filipino veterans’ strongest advocates in Congress are Asian American, including Senator Daniel Inouye and Senator Daniel Akaka, both Japanese American and both from Hawaii.

But the biggest change comes with the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. The law formally acknowledges that the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II was “a grave injustice…motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” In addition to issuing a public apology to those who were interned, the law also provides for $20,000 payments, or reparations, to each living survivor.

The Civil Liberties Act is a model for what might be possible by going through Congress. Many of its Congressional champions, like Senator Daniel Inouye and Senator Daniel Akaka, are sympathetic to Filipino veterans. But most other members of Congress are clueless. They don’t know the story of Filipino veterans and the terms of the Rescission Act. Many aren’t even aware of the colonial history between the Philippines and the U.S., or why Filipinos were serving in the U.S. armed forces during World War II.

Getting Congress to act is slow; Senator Inouye first called for a commission to study Japanese internment in 1979. Four years later, after holding hearings in 20 cities and collecting testimony from more than 750 witnesses, the commission issued a report recommending reparations. But it took another five years to rally the grassroots support to pressure Congress to pass a bill. Filipino veterans are aging; can they wait another eight or ten years, on top of the forty years that have already passed?

To be successful, Filipino veterans will have to educate members of Congress. Congress people need to understand the complexity of the Rescission Act, how it affected benefits and pensions, as well as immigration. There’s also the issue of right and wrong; so long as the Rescission Act is in place, the position of the U.S. is that Filipinos who had served under the American flag during World War II are somehow less than other soldiers. Filipino veterans are seeking equity as well as justice.

You’re an activist in the late 1980s. How do you get Congress to act?

- Get a Congressional advocate to introduce a bill to repeal the Rescission Act. The U.S. needs to make it clear that it was wrong and the U.S. made a mistake. Once the law is repealed, Filipino veterans can start making veterans claims.

- Focus on changing immigration laws so that Filipino veterans can immigrate to the U.S. if they desire. This will at least help reunite families and, unlike benefits, doesn’t cost the government anything.

- Focus on educating members of Congress about the history of U.S.-Philippines relations, and the complicated terms of the Rescission Act. Organize advocacy visits in Washington, D.C. and force members to look veterans in the face and hear their stories. If members don’t understand the issue, they won’t vote on any bill favorably, especially if it costs money.

- Rally grassroots supporters to call their members of Congress. Without pressure from the outside, Congress won’t feel any urgency about the issue. Remind Congress that the Filipino American community is paying attention and its numbers are growing. Get major veterans groups, like the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, to take up the cause of Filipino veterans.

- Practice acts of nonviolent civil disobedience. Organize sit-ins and marches, in front of the White House and on Capitol Hill, in Washington, D.C. and in places like California with large populations of Filipino Americans. Aging veterans can lead the way, with the back-up of college students and other activists. Draw attention and make things uncomfortable for those who ignore Filipino veterans.

- Something else. (In your group, propose an alternative solution.)

Scenario 4: The Immigration Act of 1990

Forty-five years after the end of World War II, Congress finally passes a law concerning Filipino veterans. The Immigration Act of 1990, signed into law by President George H.W. Bush, includes a provision that allows for the naturalization of Filipino World War II veterans who had been excluded by the terms of the Rescission Act. About 50,000 living Filipino veterans can now become U.S. citizens if they want to.

But because the 1990 Act is an immigration law and not a spending bill, it leaves veterans benefits untouched. To get benefits, Congress will have to pass a separate bill and it will cost U.S. taxpayers money. The Rescission Act is still on the books, too; the U.S. hasn’t acknowledged any wrongdoing or injustice. It feels like “half a loaf.”

The World War II generation is aging; many veterans are dying before they get any sort of justice from the U.S. government. Citizenship isn’t everything, but it could take years (if ever) before Congress does anything else. Not enough Congress members understand the history and some are outright hostile to the idea of paying for veterans benefits.

You’re a Filipino veteran in 1990. What do you do?

- Apply for citizenship. After 45 years, you’ve finally gotten at least one of the benefits that was owed to you for your service during the war. Also, as a citizen, you can bring over other members of your family, since U.S. immigration law prioritizes family reunification.

- Hold out. It’s unfair to accept “half a loaf.” The U.S. has broken its promises and it’s a matter of honor to hold out for pensions, healthcare and all of the benefits other World War II servicemen got. Plus, there’s the possibility that accepting the “half loaf” now may prevent future progress on benefits in the future.

- Step up the pressure by using more confrontational tactics. Citizenship isn’t enough. Besides, without pensions some veterans will struggle to make ends meet in the U.S. Also, despite the support of Senator Inouye and others, some members of Congress are still resistant to paying for benefits for Filipino veterans; there’s more that activists can do to force the issue.

- Something else. (In your group, propose an alternative solution.)

Scenario 5: Grassroot tactics

The Immigration Act of 1990 enables Filipino veterans to apply for U.S. citizenship. About 25,000 veterans do so. But when it comes to passing a spending bill to provide benefits to veterans, Congress clenches its fists.

Now a new generation of activists, many of them college students and the grandchildren of veterans, are getting engaged in the fight. Raised in the United States, never living under colonial rule, they question the United States’ condescending relationship to the Philippines. If aging veterans, many of them in wheelchairs or on crutches, can engage in protests and acts of civil disobedience, why can’t they? Veterans have been patient, using diplomacy and the courts to try to press their case. For more than ten years they’ve worked with sympathetic members of Congress to try to change the law, while educating others so they understand the issues. Is it time to take things to the next level? Or, after more than fifty years, is it time to back off and focus on other issues in the Filipino American community?

What tactics might move the public to really see Filipino veterans and make the United States change its mind? Are protestors, some in the 70s and 80s, some in college, willing to get arrested? Is it worth the risk of angering powerful decision-makers in Congress by engaging in more confrontational tactics?

A particularly inflexible opponent is Representative Bob Stump. He’s the chair of the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, and he has a lot of power to decide whether bills that include funding for Filipino veterans benefits can move forward. Even if Filipino veterans can get bipartisan support for their cause—and by the mid-1990s, they have—Representative Stump will have to see the light.

You’re an activist in 1997. A new Congressional term has just started. Veterans are aging and dying off. It’s starting to feel like now or never. What do you do?

- Accept that there isn’t Congressional support for spending money on veterans benefits for Filipinos. After more than 50 years, now that veterans are dying off, turn your attention to educating the general public about their service, by changing school curriculum, creating exhibits or building memorials.

- Push for the repeal of the Rescission Act. As long as it remains on the book, it’s a stain on America and will prevent further Congressional action on behalf of Filipino veterans.

- Seek a formal declaration of apology, but prepare to let the issue of veterans benefits drop. Citizenship for those veterans who want it and recognition that the U.S. was unjust are still major accomplishments.

- Organize marches and sit-ins in and in front of government buildings. Show up to V.A. offices and the Capitol building. Simultaneously, stage protests in high-profile places like MacArthur Park in Los Angeles, named for General Douglas MacArthur and near where a lot of Filipino Americans live. Do this while continuing to visit Congress people and try to educate them on the history of Filipino veterans and the Rescission Act.

- Chain yourself to the gates of the White House and start a hunger strike. The stakes are high and it’s time to take things to the next level. Less extreme protest tactics don’t seem likely to change anything.

- Show up to public meetings, including those with V.A. officials and hearings of the Veterans Affairs Committee, to ask disruptive questions and demand benefits. If necessary, confront Representative Stump in the halls of Congress, even though before now activists have patiently tried to educate him and other members and maintain a spirit of decorum.

- Something else. (In your group, propose an alternative solution.)